Photo: Shutterstock.

an apple and satellite-based broadband service Starlink each recently took steps to address new research about the potential security and privacy implications of how their services geo-locate devices. Researchers from University of Maryland they say they rely on publicly available data from Apple to track the location of billions of devices around the world – including non-Apple devices like Starlink systems – and found they can use this data to monitor the destruction of Gaza, as well as movements and more. military ownership cases in Russia and Ukraine.

At issue is the way Apple collects and publicly shares information about the precise location of all Wi-Fi access points seen by its devices. Apple collects this location data to provide Apple devices with a more crowded, low-power alternative to constantly requesting global positioning system (GPS) coordinates.

Both Apple and Google work on their own Wi-Fi-based Positioning Systems (WPS) that receive specific hardware identifiers from all wireless access points that come within range of their mobile devices. Both recorded the Media Access Control (MAC) address used by a Wi-FI access point, known as a Basic Service Set Identifier or BSSID.

From time to time, Apple and Google mobile devices will broadcast their locations — by querying GPS and/or using cell towers as beacons — and any nearby BSSIDs. This combination of data allows Apple and Google devices to see where they are within a few meters or meters, and it is what allows your mobile phone to continue showing the route you have planned even when the device cannot get a fix on the GPS.

With Google’s WPS, a wireless device sends a list of nearby Wi-Fi access points and their BSSIDs and signal strengths — via an application programming interface (API) request to Google — to which WPS responds with the device’s computer location. Google’s WPS requires at least two BSSIDs to calculate a device’s approximate location.

Apple’s WPS also accepts a list of nearby BSSIDs, but instead of compiling the device’s location based on a set of monitored access points and their signal strength that are not received and reporting that result to the user, Apple’s API. will return the geolocation of over 400 BSSIDs that are closest to the requested one. It then uses about eight of those BSSIDs to calculate the user’s location based on known landmarks.

Basically, Google’s WPS aggregates the user’s location and shares it with the device. Apple’s WPS provides its devices with a large enough amount of data about the location of known access points in the area that the devices can perform such measurements on their own.

That’s according to two researchers from the University of Maryland, who say they can use the verbosity of Apple’s API to track the movement of individual devices in and out of almost any defined location in the world. The UMD couple said they spent a month early in their research querying the API, asking it for more than a billion randomly generated BSSIDs.

They learned that while nearly three million of those randomly generated BSSIDs are known to Apple’s Wi-Fi geolocation API, Apple also retrieved some 488 million BSSID locations already stored in its WPS from another lookup.

UMD Professor David Levin and a Ph.D Erik Rye have found that they can largely avoid requesting unassigned BSSIDs by checking the list of BSSID ranges provided by specific device manufacturers. That list is maintained by Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), which also sponsors a privacy and security conference where Rye is expected to present UMD research later today.

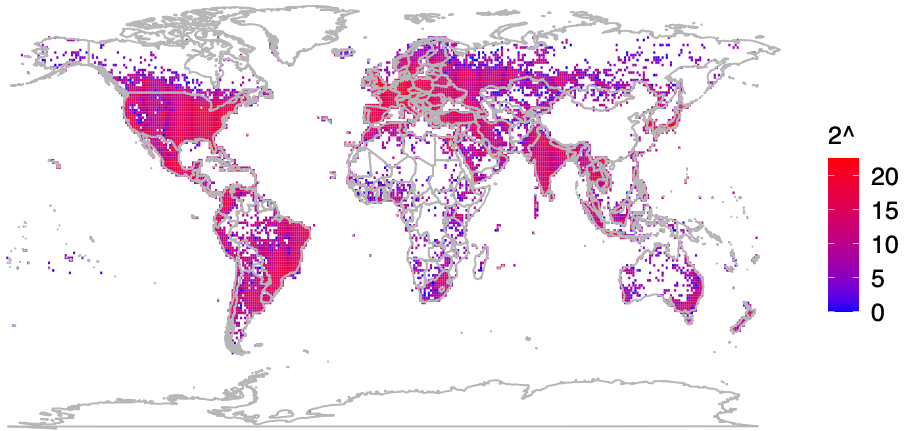

Sorting out the locations returned by Apple’s WPS between November 2022 and November 2023, Levin and Rye realized they had a close-up global view of the locations connected to more than two billion Wi-Fi access points. The map showed access points geographically located in almost every corner of the world, except for the rest of China, the vast deserts of central Australia and Africa, and the depths of the rainforests of South America.

A “heatmap” of BSSIDs the UMD team said they found by randomly guessing the BSSIDs.

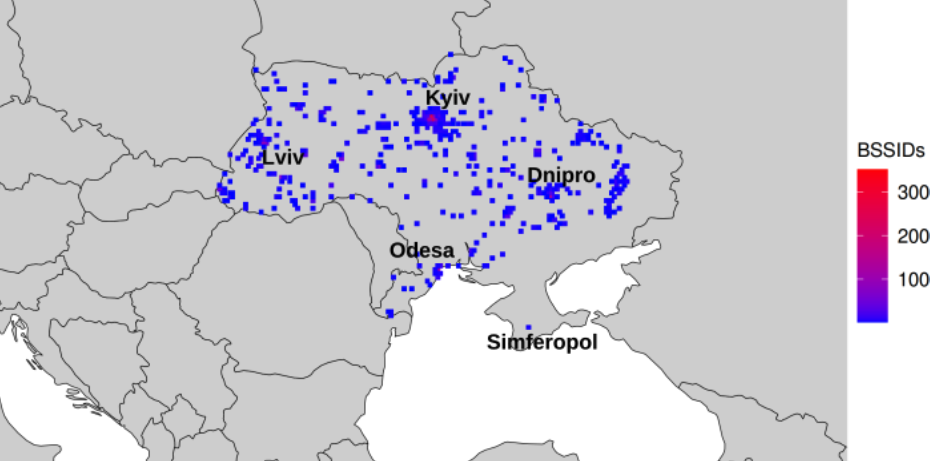

The researchers say that by logging or “geofencing” certain small regions identified by Apple’s location API, they can monitor how Wi-Fi hotspots move over time. Why might that be a big deal? They discovered that by geofencing the disputed territories active in Ukraine, they were able to determine the location and movement of Starlink devices used by both Ukrainian and Russian forces.

The reason they’re able to do that is that each Starlink terminal — the container and associated hardware that allows a Starlink customer to receive Internet service from a collection of orbiting Starlink satellites — includes its own Wi-Fi access point, its own point of entry. automatically identified by any nearby Apple devices with location services enabled.

Heat map of Starlink routers in Ukraine. Photo: UMD.

A team from the University of Maryland visited various conflict zones in Ukraine, and identified at least 3,722 Starlink terminals located in Ukraine.

“We find what appear to be personal devices brought by soldiers to war zones, revealing forward deployment locations and military positions,” the researchers wrote. “Our results also show people who have left Ukraine for various countries, confirming public reports where Ukrainian refugees have resettled.”

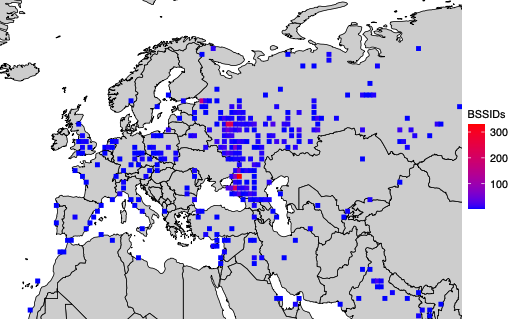

In an interview with KrebsOnSecurity, the UMD team said it discovered that in addition to exposing the Russian military’s pre-deployed sites, location data makes it easier to see where devices in competing regions come from.

“This includes residential addresses all over the world,” said Levin. “We also believe that we can identify people who have joined the Ukrainian Foreign Legion.”

A simplified map of where BSSIDs entering the Donbas and Crimea regions of Ukraine originate. Photo: UMD.

Levin and Rye said they shared their findings with Starlink in March 2024, and that Starlink told them the company began sending software updates in 2023 that forced Starlink access points to program their BSSIDs.

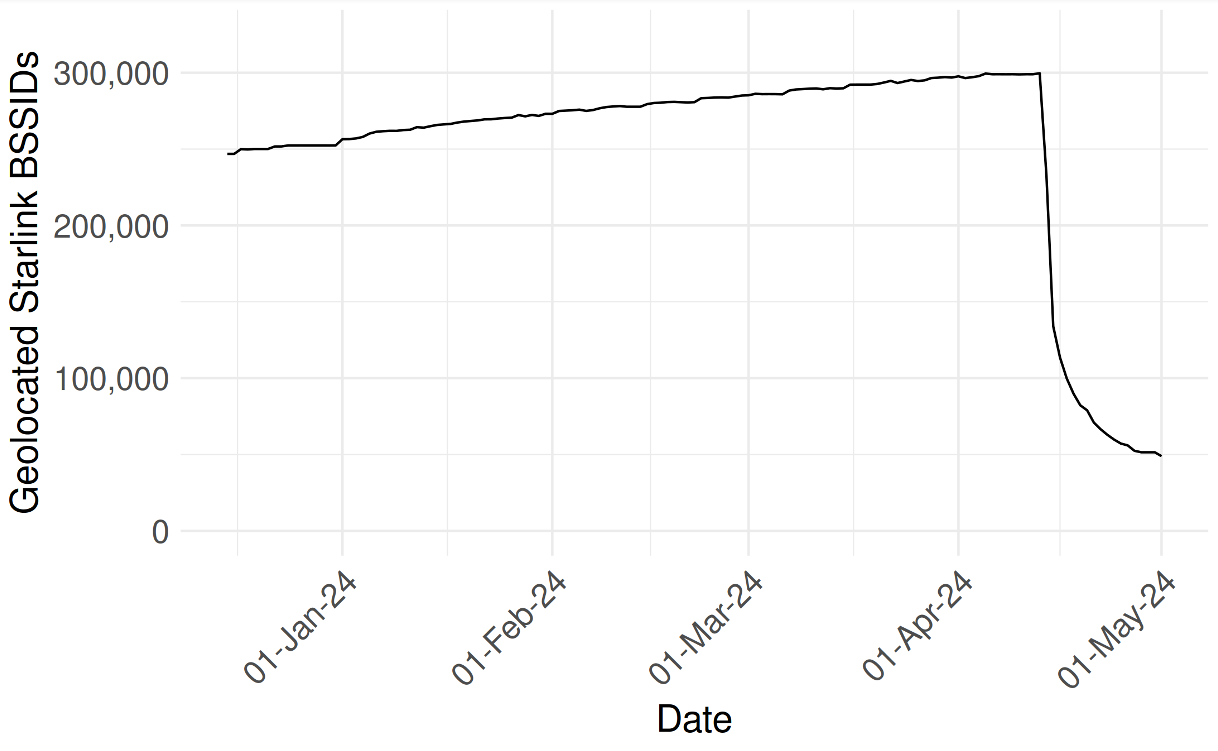

Starlink’s parent, SpaceX, did not respond to requests for comment. But researchers have shared an image they say was created from their Starlink BSSID monitoring data, showing that over the past month there has been a significant drop in the number of Starlink devices that have been geo-locatable using Apple’s API.

UMD researchers shared this image, which shows their ability to monitor the location and movement of Starlink devices with a BSSID that has dropped dramatically over the past month.

They also shared a written statement they received from Starlink, which acknowledged that Starlink User Terminal routers initially used a fixed BSSID/MAC:

“At the beginning of 2023 a software update was released that randomized the main router’s BSSID. Subsequent software releases included BSSID randomization of WiFi repeaters associated with the main router. Software updates that include the iterative randomization function are currently being rolled out regionally. We believe that the data described in your paper is based on Starlink core routers and/or repeaters that were queried prior to receiving these random updates. “

The researchers also focused their geofencing on the Israel-Hamas war in Gaza, and were able to track the migration and disappearance of devices throughout the Gaza Strip as Israeli forces cut off power from the country and bombing campaigns took out critical infrastructure.

“As time goes on, the number of geolocatable Gazan BSSIDs continues to decrease,” they wrote. “At the end of the month, only 28% of the original BSSIDs were still available on Apple WPS.”

Apple did not respond to requests for comment. But in late March 2024, Apple quietly modified its privacy policy, allowing people to opt out of having the location of their wireless access points collected and shared by Apple – by adding “_nomap” to the end of the Wi-Fi access point name (SSID).

Apple updated its privacy and location services policy in March 2024 to allow people to opt out of having their Wi-Fi hotspot identified by its service, by adding “_nomap” to the network name.

Rye said Apple’s response addressed the most pressing aspect of their research: That there was previously no way for anyone to opt out of this data collection.

“You may not have Apple products, but if you have an access point and someone around you has an Apple device, your BSSID will come through. [Apple’s] database,” he said. “What is important to note here is that all access points are tracked, regardless of whether they are using an Apple device or not. It was only after we disclosed this to Apple that they added the ability for people to log out. “

The researchers say they hope Apple will consider additional safeguards, such as effective ways to limit abuse of its local API.

“It’s a good first step,” Levin said of Apple’s March privacy update. “But this data represents a serious privacy risk. I hope that Apple will put some restrictions on the use of its API, such as limiting the level of these queries so that people don’t collect large amounts of data like we did. “

The UMD researchers said they left some details out of their research to protect the users they were able to follow, noting that the methods they used could pose a risk to those fleeing abusive relationships or abusers.

“We see routers moving between cities and countries, possibly representing the relocation of their owners or business transactions between an old and a new owner,” they wrote. “While there isn’t really a 1-to-1 relationship between Wi-Fi routers and users, home routers typically have only a few. If these users are vulnerable people, such as those fleeing intimate partner violence or a criminal, their route once online can reveal their new location.”

The researchers said that Wi-Fi access points that can be created using a built-in cellular modem do not pose a local privacy risk to their users because the hotspots connected to the cell phone will choose a random BSSID when activated.

“Today’s Android and iOS devices will choose a random BSSID when you go into hotspot mode,” he said. “Hotspots already implement very strong privacy protection recommendations. Other types of devices don’t do that.”

For example, they found that some commonly used travel routers include potential privacy risks.

“Because walkways are often used in campgrounds or boating, we see a large number of them traveling between campgrounds, RV parks, and marinas,” the UMD duo wrote. “They are used by tourists traveling between residences and hotels. We have evidence of their use by members of the military as they move from their homes and bases to war zones. “

A copy of the UMD study is available here (PDF).

Source link