Yves here. Although the AMA played a major role in setting up alternative forms of public health care, they were far from the only bad actors. It would be unfortunate if this description of the AMA’s successful tactics were to obscure the role of American labor unions. They were also against government-provided health care. They wanted it to be a significant bennie contract to justify the need for union negotiations as well as union money. Note, there are many ways that unions help workers, as we can see from overseas unions not collapsing in large numbers across Europe after those countries implemented their government paid laws. So the union’s behavior was particularly disgraceful as it benefited the leadership while not helping the rank and file and hurting the masses of Americans.

And while doctors are getting more information about the horrible crapification of American medicine, visited upon them and patients, it’s not like the current generation of doctors has been part of a campaign against the government. This is the professional version of children paying for the sins of their fathers.

By Marcella Alsan, Angelopoulos Professor of Public Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School; Yousra Neberai, Graduate student in Public Policy Harvard University; and Xingyou Ye, PhD Student Princeton University. Originally published at VoxEU

The US health care system depends on an over-subsidized and under-regulated private sector, and despite living in the richest country in the world, millions of Americans remain uninsured, uninsured, or unsure of their coverage. This column examines the rise of private health insurance after WWII, when the American Medical Association – an interest group representing doctors – funded a national campaign against National Health Insurance. Directed by the country’s first political public relations firm, the campaign used extensive advertising to associate the NHI with socialism and private insurance and the ‘American Way’.

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) designed by the UN have advanced the goal of achieving universal health coverage (UHC) in all countries by 2030 (Eozenou et al. 2023). This goal has been achieved by many high-income countries, but the notable exception is the US. Despite living in the richest country in the world, millions of Americans remain uninsured, underinsured, or uncertain about their coverage (Blumenthal and Collins 2022, Scott 2023a). Medical debt continues to be the leading cause of personal bankruptcy, and US performance on several key health outcomes is consistently below that of peer nations (Schneider et al. 2021, Kluender et al. 2021, Papanicolas et al. 2018). Recently, prominent health economists point to the US health care system, with its reliance on a heavily subsidized, poorly regulated private sector, as a key part of the problem (Case and Deaton 2020, Einav and Finkelstein 2023).

In a recent paper (Alsan et al. 2024), we step back from this current debate and seek to understand how the US has developed its complex health care system. Common explanations include the history of individual behavior, union negotiations, inflationary pressures, or favorable tax treatment of employer-sponsored health insurance (Scott 2023b). We investigate another possible influence: a massive post-WWII marketing campaign sponsored by an interest group representing doctors – the American Medical Association (AMA) – in collaboration with other industries. The campaign was managed by the world’s first political public relations firm, Whitaker and Baxter’s (WB) Campaigns Inc. New Yorker Profile of Whitaker and Baxter (Lepore 2012) – to our knowledge, our paper provides the first rigorous analysis of how interest group campaign financing, which relied heavily on indirect voter lobbying, shaped the state of health insurance over time. critical time.

The campaign came quickly in response to what the AMA described as the “Armageddon moment”. The reason for the AMA’s alarm was many: first, foreign events – in particular, the introduction of the National Health Service (NHS) in the UK – provided an example of publicly funded health care from a country that shares the same language and legal culture. Second, the shocking 1948 election of Harry Truman brought a staunch supporter of national health insurance into the White House and a large Democratic majority in Congress – ensuring that the topic would be on the legislative agenda. Third, Americans were very fond of national insurance and the main reason was said to be the concern of the less fortunate.

The AMA-WB campaign had two main components. First, they used mass advertising to associate the NHI with socialism, while the option of private (or voluntary) insurance was described as the “American Way”. These AMA advertising efforts were supplemented by concerted advertising from other industries that feared a return to wartime price controls. Additionally, the strategy called for AMA physicians to discuss private health insurance with their patients and distribute pamphlets echoing each individual’s advertising message (see Figure 1). Through local and state medical associations, doctors looking to cover medical expenses had organized their own insurance product, known as Blue Shield, and were eager to sign up. In total, nearly $250 million (in current terms) was spent on canvassing voters, an unprecedented amount at the time. Doctors were also instructed to use their reputation to urge local civil society organizations to make decisions against national health insurance.

Figure 1 Campaign leaflets

Notes: Figure shows two examples of pamphlets distributed by physicians affiliated with the AMA during the campaign.

The source: Whitaker and Baxter Campaigns, Inc. archives.

We use several recently digitized data sources – including databases from Campaigns Inc., digitized medical directories from the AMA, hospital directories from the American Hospital Association (AHA), invoices from the advertising firm Lockwood-Shackelford , and newspaper references – we rebuild the AMA -WB campaign momentum. The strategy presented in the campaign documents did not target specific areas as it required a quick response, and modern statistical methods of market analysis had not yet been developed. In addition, the medical insurance market was far from saturated as it was a new product. Instead, Campaigns Inc. relies on existing relationships and resources: tapping an advertising agency it has used for years and pushing private insurance sales through AMA membership. Empirically, we find that, depending on factors that may clearly influence the demand for a private health insurance product – such as income, unions, and hospitals – exposure to the campaign is unrelated to the pre-existing (low) level of private health insurance. Our primary outcomes of interest are enrollment in private health insurance, which we digitized from recently obtained Blue Shield reports, and public opinion data from Gallup Polls. Our analysis ends in 1954, when the federal government classified health insurance payments as tax-free, and businesses began to compete more with Blue Shield.

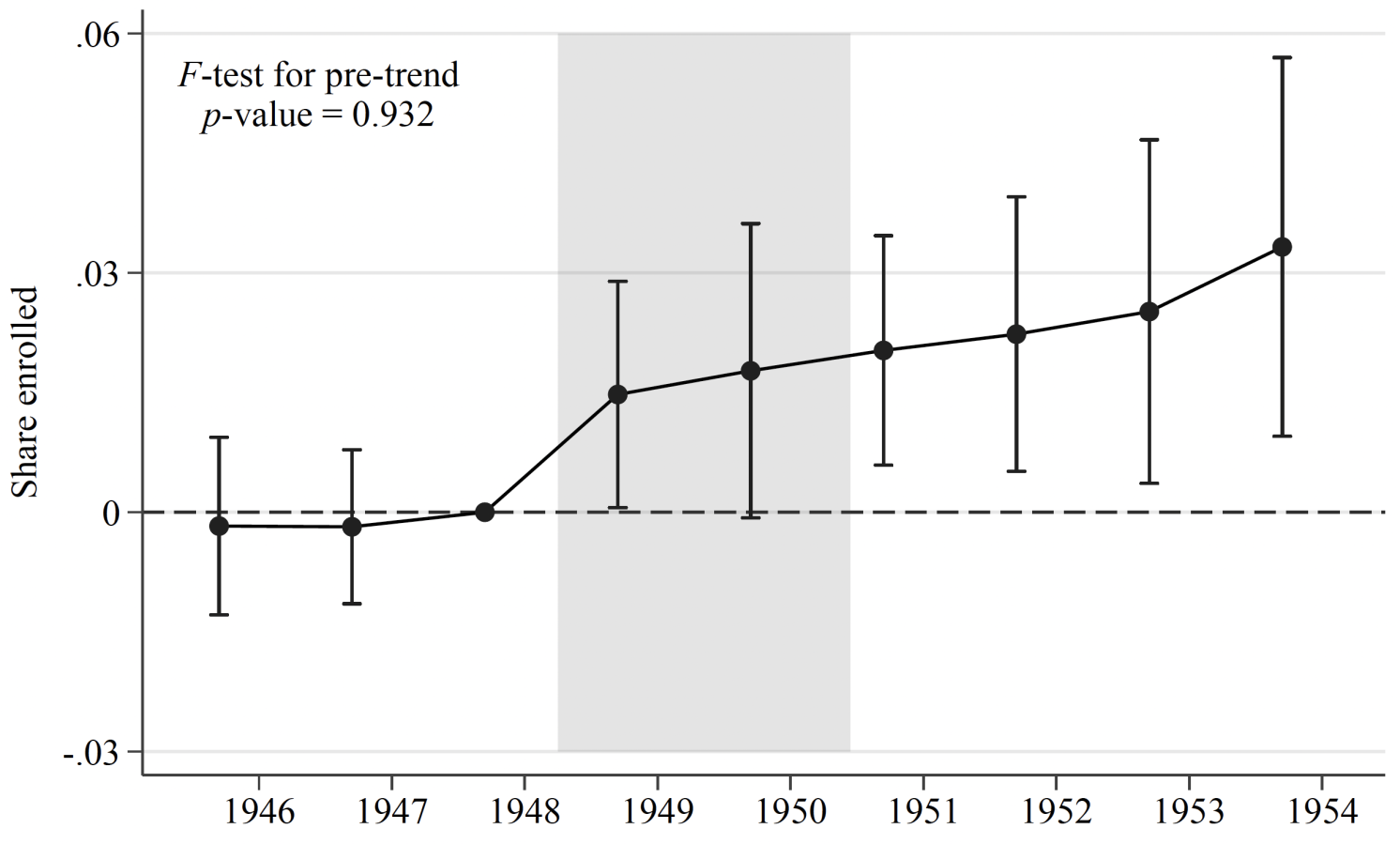

We find that one standard deviation of AMA-WB campaign exposure explains a 20% increase in private health insurance enrollment over this period (Figure 2), and a corresponding decrease in public opinion support for national health insurance legislation. The results on public opinion are remarkably similar across broad individual characteristics – however, respondents who voted Republican in the previous election appear to have been influenced by the campaign, perhaps indicating that the ideological framework is more favorable to members of that party. We also find suggestive evidence that the campaign changed how legislators interpreted the proposed health insurance law, using descriptors such as “mandatory” as opposed to “national” in text taken from the Congressional Record. Echoes of this campaign can be seen in Gallup polls until questions about national health insurance are no longer asked as the issue moves through the legislative process. Taken together, the findings provide evidence of an underappreciated contributing factor to why the US has developed its own unique and complex health care environment. Although it is a historical paper, this finding may take on a new importance given recent evidence about the importance of health insurance to improve labor productivity, reduce health inequalities, and reduce mortality (Baten et al. 2023, Del Valle 2015, Miller et al. 2021, Goldin et al.

Figure 2 Impact of the campaign on private health insurance enrollment

Notes: Event study coefficients for statistical programs of campaign exposure to private health insurance enrollment between 1946 and 1954. See Alsan et al. (2024) for more details.

However, why did the US not change course in the following years? Our paper cannot easily address persistence given the limitations of the data, but we offer several reasons why the case for national health insurance was weakened significantly after the AMA-WB campaign. First, as middle-class Americans became self-sufficient and ultimately dependent on private aid, public elections became more useful to many voters. Indeed, this was the clear intention of offering a private option to begin with, according to campaign documents. Second, for-profit insurance firms are increasingly entering the healthcare space: next to pharmaceutical companies, hospitals, and specialist doctors, these groups continue to benefit financially and are an obstacle to deviating from the status quo (Acemoglu et al. 2021). Third, the ideological debate that state involvement in health care always leads to socialism is still common in the US – whenever reforms are proposed, the opposition’s response often explicitly mentions the fear of socialism (see for example Gruber 2011). In other words, the narrative developed and promoted by the AMA-WB campaign remains entrenched in US policy debates, with consequences for national health and the stability of insurance markets (Krugman 2021, Bursztyn et al. 2020).

See the original post for clues

Source link