Yves here. Those who follow climate change issues casually have heard of feedback loops such as melting permafrost leading to methane emissions that raise carbon levels. This post describes local examples of human activities that impact climate on a national scale.

By Kyle Hilburn, Research Scientist in Atmospheric Science, Colorado State University. Originally published on The Conversation

Wildfire whirlwinds, firestorms, severe thunderstorms: When fires get big and hot enough, they can create their own weather.

In these extreme fire conditions, firefighters’ normal methods of direct fire control do not work, and wildfires burn out of control. Firefighters saw many of these hazards in the massive Park Fire near Chico, California, in the summer of 2024.

But how can fire create weather?

I am an atmospheric scientist who uses data collected by satellites in weather forecasting models to better anticipate extreme fire weather conditions. Satellite data shows that fire-generated thunderstorms are more common than anyone realized a few years ago. Here’s what happens.

Wildfire and Climate Links

Imagine a wild landscape with dry grass, brush and trees. A spark strikes, perhaps from lightning or a tree branch hitting a power line. If the weather is hot, dry and windy, that spark can quickly ignite a wildfire.

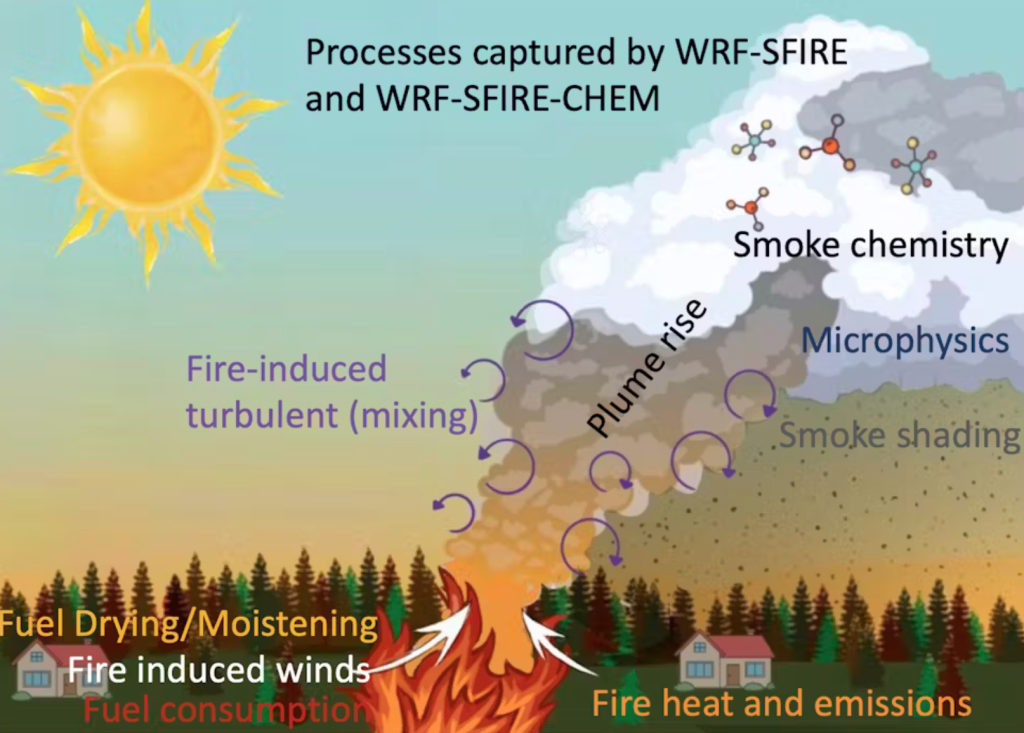

When vegetation burns, more heat is released. This heats the air near the ground, and that air rises like a hot air balloon because hot air is less dense than cool air. Cool air then rushes in to fill the space left by the rising air.

This is how wildfires develop their wind patterns.

What happens next depends on the stability of the atmosphere. If the temperature cools rapidly with altitude, then the rising air will remain warmer than its surroundings and will continue to rise. If it gets high enough, the moisture will condense, forming a cloud known as pyrocumulus or flammagenitus.

If the air keeps rising, at some point the condensed moisture will freeze.

If a cloud contains both liquid water and ice particles, the collision of these particles can lead to a separation of electric charge. If the charge buildup is large enough, an electrical discharge – better known as lightning – will occur to reduce the charge.

Whether a fire cloud becomes a thunderstorm depends on three key factors: source of lift, instability and moisture.

Dry Lightning

Wildfire areas usually have limited moisture. If conditions in the lower atmosphere are dry, this can lead to what is known as dry lightning.

No one who lives in a wildfire prone area wants to see dry lightning. It occurs when a thunderstorm produces lightning, but the rain evaporates before it reaches the ground. That means there is no rain to help put out any fires started by lightning.

The fire is blowing

As air rises in the atmosphere, it may encounter different wind speeds and directions, a condition known as wind shear. This can cause the air to circulate. Updrafts can tilt the spin vertically, similar to a tornado.

These firestorms can have strong winds that can spread burning ash, creating new areas of fire. They are usually not true tornadoes, however, because they are not associated with rotating thunderstorms.

Decay Storms

Eventually, the thunderstorms caused by the forest fire will begin to die down, and what went up will come back down. A downdraft from a decomposing storm can produce variable winds on the ground, further spreading the fire in areas that can be difficult to predict.

When fires create their own climate, their behavior can be unpredictable and erratic, which only increases their threat to residents and firefighters fighting the blaze. Anticipating changes in fire behavior is critical to everyone’s safety.

Satellites Show Weather Caused by Fires Are Very Rare

Meteorologists saw the power of fire to create thunderstorms in the late 1990s. But it wasn’t until the launch of the GOES-R Series satellites in 2017 that scientists had the high-resolution images needed to see whether fire-induced weather is actually a regular phenomenon.

Today, these satellites can alert firefighters to new fires even before calls to 911. That’s important, because there is an increasing trend in the number, size and frequency of wildfires across the United States.

Climate Change and Increasing Fire Risks

Heat waves and the risk of drought have been increasing in North America with rising global temperatures, which often leave dry land and forests burned. And climate model tests show that human-caused climate change will continue to increase that risk.

As more people move into fire-prone areas in this hot climate, it’s no surprise that the risk of fires starting and spreading increases. As fires come with devastating risks that persist long after the fire is out, such as burn-scarred areas are more prone to landslides and debris flows that can affect water quality and the environment.

It is important to remember that fire is a natural part of the Earth system. Communities can reduce their vulnerability to fire damage by building shelters and firebreaks and making homes and property less vulnerable. Fire extinguishers can also reduce fuel loads around a prescribed fire.

As fire scientist Stephen J. Pyne writes, we as humans will have to adjust our relationship with fire in order to learn to live with fire.

Source link