That’s the subject of an article by Christopher Condon, in Bloomberg a few days ago. What is the evidence? Figure 1 shows the trade-weighted dollar-denominated CPI.

Figure 1: CPI decreased by the trade-weighted dollar (blue), and unit labor costs decreased by the trade-weighted dollar (tan). The NBER has defined recession days as shaded in gray. Source: OECD via FRED.

Unit labor cost (ULC) minus the real exchange rate is closer to the concept of competitiveness than CPI reduction (see Chinn (OER, 2006)). That’s because the CPI measures the prices of traded and untraded goods and services, while the ULC tends to work in the manufacturing (potentially traded) sector and costs of production.

While the dollar hit a trough in 2015Q1 in terms of both measures, by 2024Q2, the truncated ULC series had risen by only 12.4% compared to 19% recorded by the truncated CPI series. Now, the reduced ULC series only includes data for countries where the required data is available, so it excludes for example China. Nevertheless, Ahn, Mano and Zhou (JMCB, 2020) show that in general the depreciated exchange rates of the ULC are the only exchange rates that consistently show positive behavior in terms of trade balances (ie, appreciation lowers the balance).

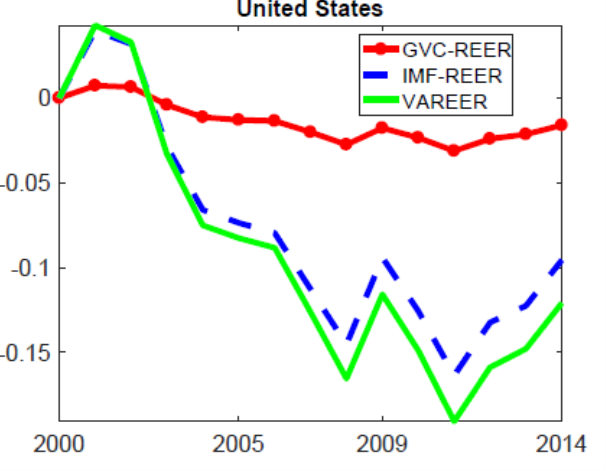

It is also true that real exchange rates often use prices or costs of final goods, rather than value added. Bems and Johnson (AEJ Macro, 2017) calculate such exchange rates. In addition, one may want to consider global value chains. Patel, Wang and Wei (JMCB, 2019) calculate value added and real exchange rates for global supply chains, up to 2014.

Source: Patel, Wang, Wei (2019).

The adjusted exchange rate of the world value chain shows much less variation than a depreciated CPI, or even a depreciated ULC. That being said, the sample ends before the dollar’s sharp appreciation in 2015.

Finally, it should be noted that any policies that Trump proposes – including tax cuts, new tariffs – are likely to result in greater appreciation, rather than less, of the dollar.

Source link