Yves here. This practice of factory construction, observed by Wolf Richter, bears watching. It’s a concrete demonstration (pun intended) that there is a major effort underway to “regenerate the coast”. However, desire and spending do not translate into results. Remember the big Foxconn factory in Wisconsin, where they took a lot of government subsidies and then gave it away. From CNBC in 2021:

Taiwanese electronics maker Foxconn has significantly delayed a planned $10 billion factory in Wisconsin.

Under the deal, Foxconn will reduce its planned investment to $672 million from $10 billion, and reduce the number of new jobs to 1,454 from 13,000.

And remember, this is an established player, as Foxconn can start and operate factories. These are not Americans who may be rushing to find the much-needed factory managers and high-level production managers.

Wisconsin at least restructured the deal and rolled back many of the funding commitments.

Similarly, Alexander Mercouris reported a long form about the failed US attempt to increase the production of 155 mm shells. In addition to the many mistakes he listed at length, the bottle always lacks a gun. There seems to be only one factory, in Poland, that makes TNT. The US had decided to get rid of TNT because it was inherently bad, but the replacement didn’t work (I’m not sure because it failed as an explosive or because it was too difficult to produce at the right scale and/or cost).

Granted, it’s a different kind of manufacturing, but I was a paper miller and my father ran paper mills. The bound paper is very strange. The coating, in his day of mineral clay, is applied when the paper is wet. Paper machines must operate with very fine tolerances or else the paper breaks, resulting in costly downtime.

Mills have to operate 24/7 except for scheduled ones because capital costs are high.

My father drove startups and turnarounds because no one else in the industry could do it. He eventually became head of production at one of the largest paper manufacturers.

The rule of thumb was that a successful start-up (for one “machine” as in a production line, cost ~$500 million in the 1970s) took two years and cost 20% of capital costs. The failed startup was a money run.

In other words, setting up factory buildings is the easy part. Keep an eye on how high the open rate and productivity is.

By Wolf Richter, editor at Wolf Street. Originally published in Wolf Street

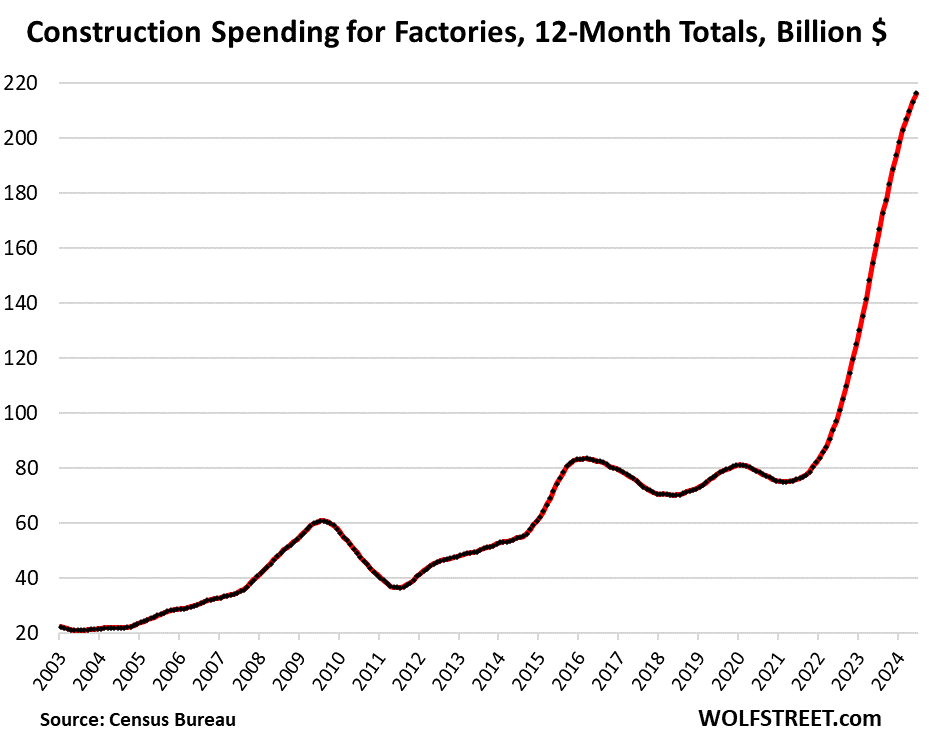

Companies invested a record $19.7 billion in June in manufacturing facilities, up 18.6% from June 2023 levels, up nearly 100% from June 2022, and up 209% from June 2019, according to the Census. Bureau today.

The total investment here includes only the actual cost of building the building, not the cost of manufacturing and installation materials that can reduce the construction cost of the building. The total cost of a large chip plant may reach $ 20 billion, but the cost of construction is a very small part. Therefore the total amount invested in manufacturing plants, including equipment and installations, is very high. But here, the prices refer only to the construction of plants, and can be seen as a guiding indicator of the total investment in production.

In addition to the development of semiconductor plant construction, a large number of other manufacturing plants have been announced, and continue to be announced.

The explosion of factory construction that began in the second half of 2021 was one of the changes that came out of this pandemic where the terrible dependence of the United States on China is reflected in the large shortage of all kinds of goods, including the shortage of semiconductors, and the supply chain in an unbelievable way. and transportation chaos, which caused corporate America and policymakers to rethink the strategy of perpetual globalization.

The CHIPS Act, which was signed into law in August 2022, was part of the movement. Although the first prizes have been announced, much remains to be done, including due diligence, and the money has not yet been released. That is yet to come.

The 12-month total investment in manufacturing industries rose to $235.5 billion, up 19% from the same period last year, up 100% from two years ago, and up 217% from the same period in 2019.

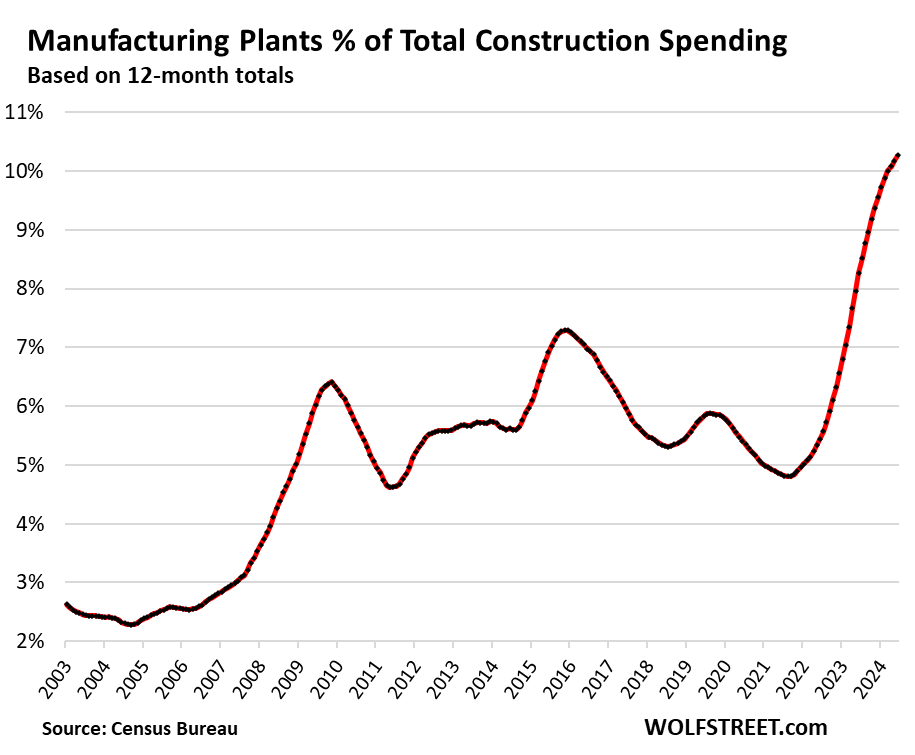

Construction costs for manufacturing facilities now make up more than 10% of total construction costs in the US, both residential and non-residential, from single-family homes to roads and power plants.

It’s all based on the principle that industrial robots cost the same in the US and China, that manual labor is part of the smallest costs in modern automated production, as well as transportation costs (which increased during the crisis) and the loss of Intellectual Property (IP). ), offered in China, and other risks must be added to the cost calculation.

In addition, the increasingly difficult and strained relationship between the US and China has exposed for all to see that the careless dependence of US companies on manufacturing in China is a serious risk, not only to companies, but also to national security.

No one is going to build a factory in the US to make low-cost products, like T-shirts. All are focused on high-value complex products, such as cars, ships, electrical and electronic products, heavy equipment and machinery, etc.

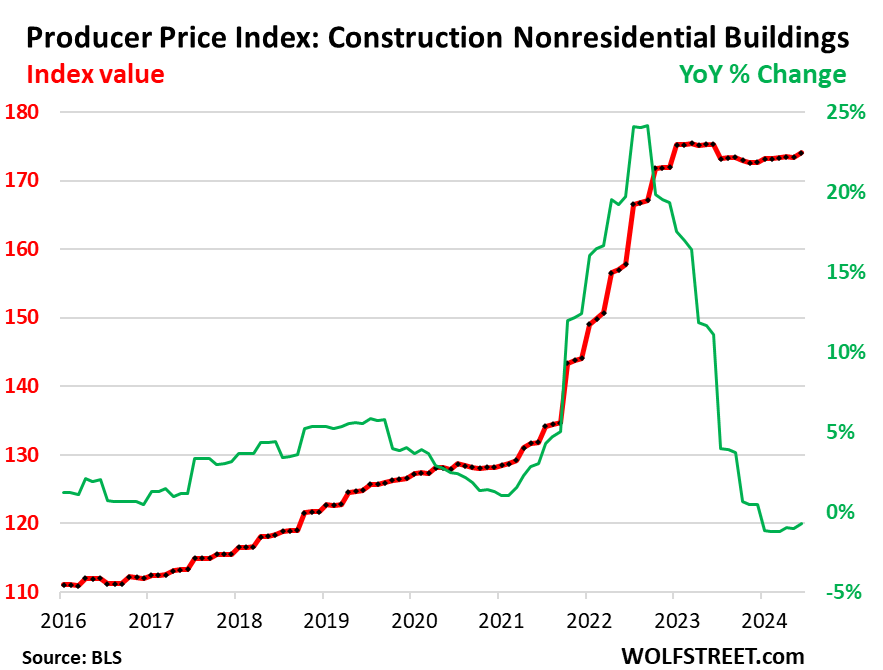

Construction Inflation Has Declined

The Producer Price Index for non-residential construction costs, after peaking in mid-2021 to 2022, began to rise in early 2023 and has been relatively flat since then (red in the chart below).

On a year-over-year basis, the PPI for non-residential construction has been flat to negative since late 2023, after rising nearly 24% in mid-2022 (green).

Source link