Harris Walz’s plan to restore grocery prices seems to consist of two parts, one of which has attracted a lot of attention (stopping price increases), and the second (not trusting food processors) has received less criticism (see agenda here). While it may be the case that grocery store chains only exercise some power, it is not clear to me that it is the most important factor in the development of grocery prices.

Here’s a picture of household food prices versus retail food prices (and processed meat prices), all log-normalized to 2021M01=0.

Figure 1: CPI household consumption (bright black), PPI food production (light blue), and PPI processed meat, poultry and fish (red), all included in logs, 2021M01=0. NBER’s highest recession dates in gray.

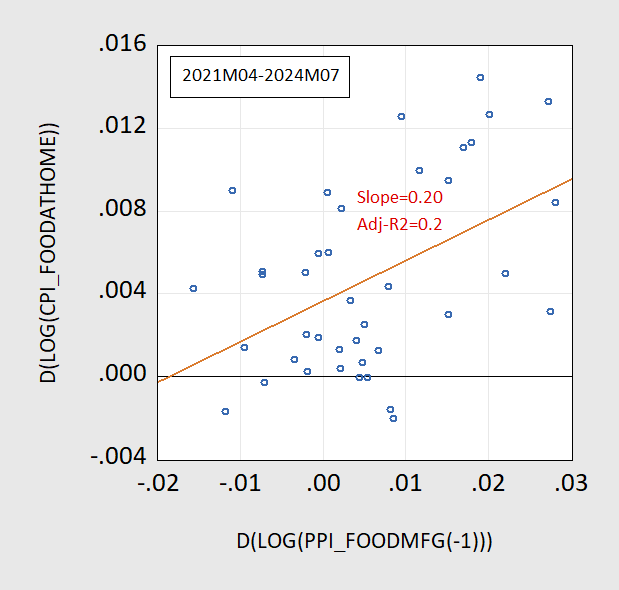

Note that the price of processed meat has increased during the pandemic, partly due to the increase in wages (due in part to the epidemic causing constraints in the labor supply). See how wages in food processing are rising as the number of foreign workers falls, here. Did higher food prices “cause” higher grocery prices? That is a difficult question to answer. One can say that from a period of one year after the trough defined by the NBER, to 2024M07, the Granger causality test rejects the null hypothesis that changes in the prices of food production do not affect changes in the food component of the CPI at 1% msl. The regression fails to reject, at 5% msl. Here’s a scatterplot of the first log difference of CPI-food at home to PPI-food mfg residual:

Figure 2: First log difference of CPI-food at home versus PPI-food lying mfg, and regression line.

Now, is the increased focus on digestion a mistake? As MacDonald, Dong and Fuglie, (2023) point out, it is not clear, at least in the pre-pandemic period.

From the paper (p.36):

The meat and poultry processing industries were transformed as ranchers built larger plants to gain economies of scale. Processors are also building strong links with the restructured livestock production sector to ensure reliable supply of livestock to keep crops at full capacity. Those changes have led to a dramatic increase in concentration, particularly in the slow-growing pork and beef industries, while also resulting in lower livestock production and slaughter costs. However, although there has been some significant consolidation among processors, most of the growth in concentration has come from the construction of new plants, or from expanding existing plants with larger processors, rather than from mergers among competitors. Despite the high levels of concentration, a study of cattle market prices prior to 2010 found limited evidence of the strength of the park market. Lower processing costs appeared to be passed on to consumers, with the resulting increased demand for beef leading to increased cattle demand and prices. There have been a few studies of the poultry or pork markets, but those studies found only small or localized effects from the concentration of prices in those industries. However, developments since 2010, which show a growing spread between processing prices paid for livestock and get meat, and new entrants in the industry, suggest that meatpackers are now able to exercise greater market power over the price of livestock than in previous decades. New entrants, and plant expansion among incumbent producers, will determine whether such market power can be maintained.

The mitigating effects from using large economies of scale versus large pricing power may lead to a small increase or even a complete decrease in product prices. However, the imposition of strict binding constraints from limited labor supply may alter that balance.

Antitrust actions are much less likely to have perverse effects on food markets than direct price controls. In any case, it’s not clear to me that direct price controls are what the Harris-Walz campaign is all about.

Source link