Lambert here: Since you, readers, are geographically dispersed, I’d like to know if you have any anecdotes to share about the thesis of this article. (Additionally, such maps are initially).

By Guyon Kim, Assistant Professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz, Cassandra Merritt, PhD candidate at the University of California, Davis, and Giovanni Peri, C. Bryan Cameron is Professor of Economics and Director of the Global Migration Center at the University of California, Davis. Originally published at VoxEU.

The evolution and changing content of work is a defining feature of advanced economies. Jobs that didn’t exist in the US before 2000, for example, now employ millions of people. This column analyzes the role of local factors and exposure to global shocks in generating ‘new work’. .

The evolution and changing content of work is a defining feature of advanced economies. The most advertised jobs in the 1990s did not exist as job qualifications in the 1950s (Atalayt al. 2020) and 63% of employment in 2018 was done in jobs that did not exist in the 1940s (Autor, Chin, Salomons, and Seegmiller, 2024). The ability of the economy to create jobs and jobs that culminate into new types of jobs – ‘new jobs’ – is essential to maintaining employment and continued economic prosperity (Umbhali, 2015). Jobs described as “data warehouse architect”, “online marketer”, “global supply chain director”, but also “health care planner”, “sommelier”, and “barista” did not exist in the US before 2000, but now use millions of people.

Recent literature has formalized the idea of changing job content through two main methods. Studies following the pioneering work of Autor et al. (2003) and Autor et al. (2008) consider work shifts between occupations characterized by different tasks or skill intensities. They suggest that work has shifted from more routine tasks to more non-routine cognitive, interpersonal, and analytical tasks. However, these studies are far from changes in job descriptions that capture the content of more detailed jobs. The second set of literature analyzed the role of technology in changing the set of jobs while simultaneously creating new job opportunities, where the intensity of these two conditions, over time, determines the rate of employment growth (Acemoglu and Restrepo 2019). However, these texts do not systematically analyze the role of local factors and exposure to global shocks (other than technology) in the production of ‘new work’.

In a recent paper (Kim et al. 2024), we present a novel measure of ‘new work’ based on the introduction of new content in job titles to answer the following questions: Is it related to specific jobs, skills, and characteristics of workers ? Is ‘new work’ associated with job growth? And what local factors and exposure to global shocks predict ‘new work?’ These are important questions to understand the recent evolution and future trends of the US labor market.

Evaluating New Work as New Content in Work Titles

Our innovative approach contributes to task switching research by identifying a ‘new task’ with semantic differences based on natural language processing methods. In doing so, we build on the pioneering concept of ‘new job’ introduced by Lin (2011) that uses additions to the Census catalog of job titles and extend the use of semantic differences to detect ‘new job’ developed by Kim (2024).

The core of our algorithm is a text analysis that transforms job titles into high-dimensional vectors to compare semantic similarities. The vectors provided by the ‘Continued Bag of Words’ algorithm are based on the probability that words in a job title appear in the same contexts as words in another job title¬ – based on millions of training documents. ‘New’ in this context means ‘far enough (by definition) from’ any existing work on the previous list. After further technical steps that support our view of ‘adequate distance’ in the quality of source documents, our method can be used to identify ‘new work’ using any comprehensive list that describes a set of jobs and activities in any economy over time. We use this method to identify ‘new occupation’ for 350 US occupation codes during the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s.

Characteristics and Geography of New Work

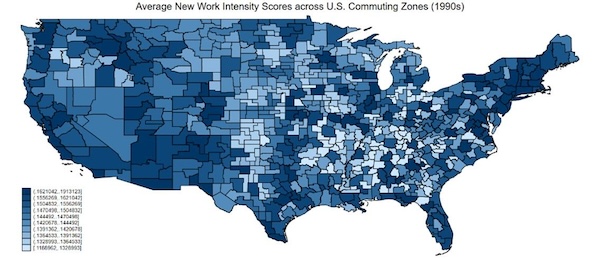

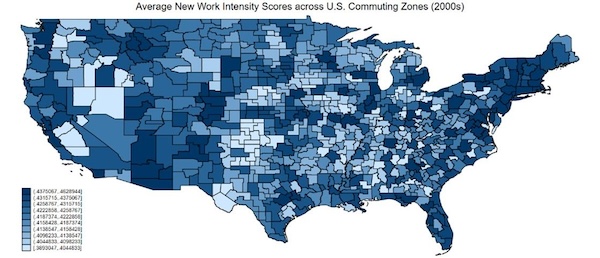

Our first findings are finding ‘new work’ across all occupations and locations. We find that ‘new work’ has a strong positive association with years of education and intensity of non-traditional cognitive and manual tasks across all occupations. We then modify our measure to capture its intensity across US transit areas based on local employment distributions in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s. Figure 1 shows the strength of the ‘new job’ in the US for each decade and shows two factors:

- Significant persistence in the area of ’new work’ over decades (eg coastal versus southern regions)

- Urban areas get more ‘new work’ (including non-coastal suburbs like Denver, Austin, and Chicago)

Across all occupations, ‘new work’ is significantly and positively associated with greater employment growth, and this association is amplified across regions, suggesting a multiplier effect of ‘new work’.

Figure 1 The geography of the ‘new job’

Panel A: 1980s

Panel B: 1990s

Panel C: 2000s

Notes: The dark shade represents the greatest intensity of ‘new work’ in the workplace.

The Role of Global Seismic and Local Factors

We then turn the analysis to what predicts ‘new work’ in all areas of travel between 1980 and 2010. We focus on two sets of economic considerations:

- Local exposure to global shocks: trade competition, new technologies (computerisation and robotics), immigration, and aging of the local population.

- Density of local factors (conserved since 1980): population density, college-educated share, labor productivity share, and industrial diversity

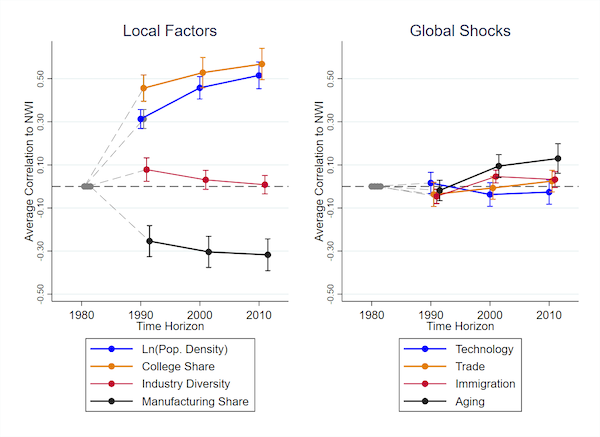

Three sets of key findings emerge. First, the geographic share of the college-educated population in the first period is the most statistically significant and economically significant predictor of ‘new employment’ (Figure 2, left). High population density and low share of manufacturing activity are the next most important predictors.

Second, exposure to global shock compared to local factors has a weaker predictive power of ‘new job’ (Figure 2, right). Population aging is the only shock that has a strong relationship with ‘new work’. In further analysis, we show that this is mainly driven by the predicted share of retired people, which suggests the important role of this group in stimulating the demand for new services. Exposure to other global shocks, however, does not show a significant correlation with ‘new employment’ on average.

Third, the importance of some global shocks is revealed when it allows for diversification across all types of jobs and locations. Exposure to technology has a positive predictive power for ‘new work’ especially based on tasks with high non-standard cognitive analysis. This type of ‘new job’ is also related to local population and population density. In addition, exposure to trade problems predicts ‘new employment’ especially in areas with high population density and high college-educated populations, which we call ‘high-skill cities’. Outside of these ‘high-skilled cities’, highly educated immigration is associated with more ‘new work’, suggesting that it is another important source of social welfare associated with ‘new work’ where the population is low.

Figure 2 How Local Factors and Global Seismic Exposure Predict ‘New Work’

Notes: Figure shows the increase or decrease in ‘new job’ capacity predicted by one standard deviation change in local factor (left) or exposure to global shocks (right) shown over the period 1980-2010.

Home Colleges and Their Role in Providing Employment

A set of predictions from our analysis highlights local population as an important determinant in stimulating ‘new work’ and mediating the role of global shocks in the capacity of domestic labor markets to create ‘new work’. Therefore, we improve the identification of the causal role of local supply of iron (IV) ratio. We analyze the effect of the 1980 college grant by using the historical presence and density of local colleges, going back to the establishment of land grant colleges before 1920. the local intensity of ‘new work’.

Our results highlight the critical importance of human provision in the creation of ‘new work’. The results suggest that highly skilled workers have a comparative advantage in creating new jobs – partly due to these local institutions adapting to the growing demands for skills – which facilitates the initiation and diffusion of ‘new work’.

Conclusions and Research Methods

A new measure of ‘new work’ in Kim et al. (2024) advances our understanding of how work evolves. The algorithm and method can be used to identify ‘new work’, based on the emergence of statistically different job titles, in all other periods of history and in other countries that can further expand and carry out this analysis.

Our preliminary analysis of local and global factors predicting ‘new work’ confirms the role of local people as an important factor (Gagliardi et al. 2024) both in generating ‘new work’ and in transforming shocks (such as trade and commercial technological change) into ‘new work’. Surprisingly, we also find that an increasing number of retirees is associated with more ‘new work’, which appears to be related to the demand for new services.

References are available at the beginning.

Source link