The proliferation of new top-level domains (TLD) weakened known security weaknesses: Many organizations set up their internal Microsoft authentication systems years ago using domain names in TLDs that did not exist at the time. That is, they keep sending their Windows usernames and passwords to domain names they don’t control and are freely available for anyone to register. Here’s a look at one security researcher’s efforts to map and reduce the size of this insidious problem.

At issue is a well-known security and privacy threat called “namespace collision,” a situation in which domain names intended for exclusive use on an internal company network end up overlapping with domains that can be resolved generally on the open Internet.

Windows computers on a private enterprise network authenticate other objects on that network using a Microsoft innovation called Active Directory, which is an umbrella term for a variety of identity-related services in Windows domains. An important part of how these things find each other involves a Windows feature called “DNS name devolution,” a type of network abbreviation that makes it easy to find other computers or servers without having to specify the full, official domain name of those resources. .

Consider the hypothetical hidden network internalnetwork.example.com: If a user on this network wishes to access a shared drive named “drive1,” there is no need to type “drive1.internalnetwork.example.com” in Windows Explorer; entering “\drive1” alone will suffice, and Windows takes care of the rest.

But problems can arise when an organization builds its Active Directory network on a domain it does not own or control. While that may sound like the way to design a corporate authentication system, remember that many organizations built their networks long before the introduction of hundreds of top-level domains (TLDs), such as .network, .inc, and .llc.

For example, the company in 1995 created a Microsoft Active Directory service around the domain company.llcperhaps thinking that since .llc wasn’t even a valid TLD, the domain would simply fail to resolve if the organization’s Windows computers were ever used outside of the local network.

Alas, in 2018, the .llc TLD was born and started selling domains. From then on, anyone who registers company.llc will be able to block that organization’s Microsoft Windows credentials, or permanently alter those connections in some way – such as redirecting them somewhere malicious.

Philippe Catureglifounder of security consultancy Seralys, is one of several researchers looking to quantify the problem of namespace collisions. As a professional penetration tester, Caturegli has long been using this vulnerability to attack certain targets that were paying to investigate cyber defenses. But over the past year, Caturegli has been slowly mapping these vulnerabilities across the Internet by looking for clues from self-signed security certificates (eg SSL/TLS certificates).

Caturegli has been scanning the open internet for self-signed certificates that point to domains in various TLDs that might attract businesses, including. .ad, .associates, .center, .cloud, .consulting, .dev, .digital, .domains, .email, .global, .gmbh, .group, .holdings, .host, .inc, .institute, .international , .it, .llc, .ltd, .management, .ms, .name, .network, .security, .services, .site, .srl, .support, .systems, .tech, .university, .win again .sinnersamong others.

Seralys has obtained certificates that refer to more than 9,000 different domains in all of those TLDs. Their analysis determined that many TLDs have more exposed domains than others, and that about 20 percent of the domains they found ending in .ad, .cloud and .group remain unregistered.

“The scale of the problem seems to be bigger than I originally expected,” said Caturegli in an interview with KrebsOnSecurity. “And while I was doing my research, I also found government agencies (foreign and domestic), important infrastructures, etc. with ill-prepared clothes.”

REAL TIME CRIME

Some of the TLDs listed above are not new and are compatible with country code TLDs, such as .it in Italy, too .advertisementthe TLD for the country code of the small nation of Andorra. Caturegli said many organizations no doubt viewed a domain ending in .ad as an internal-friendly abbreviation Aactive Ddirectory setup, while not knowing or worrying that someone could actually register such a domain and grab all their Windows credentials and any unencrypted traffic.

When Caturegli receives an encryption certificate it is continuously applied to the domain memrtcc.ad, the domain was still available for registration. Then he learned that ad registration required potential customers to show a valid trademark for the domain before it could be registered.

Undeterred, Caturegli found a domain registrar who would sell him the domain for $160, and handle the trademark registration for another $500 (in a subsequent .ad registration, he found a company in Andorra that could process a trademark application for half that amount).

Caturegli said that soon after setting up the DNS server for memrtcc.ad, he began receiving a flood of communications from hundreds of Microsoft Windows computers trying to authenticate to the domain. Each request had a Windows username and password prompt, and when Caturegli searched for usernames online, he concluded that they all belonged to the Memphis, Tenn., police department.

“It looks like every police car there has a laptop in the car, and they’re all attached to this memrtcc.ad site that I’m running now,” Caturegli said, noting with surprise that “memrtcc” stands for “Real Time Crime Center of Memphis.”

Caturegli said setting up the memrtcc.ad email server record caused him to start receiving automated messages from the police department’s IT help desk, including trouble tickets about the city’s Okta authentication system.

Mike Barlowinformation security manager for the City of Memphis, confirmed that Memphis Police systems share their Microsoft Windows credentials with the site, and that the city was working with Caturegli to have the site transferred to them.

“We are working with the Memphis Police Department to at least defuse this issue for now,” Barlow said.

Domain managers have long been encouraged to use it .of the area internal domain names, because this TLD is reserved for use by local networks and cannot be transmitted over the open Internet. However, Caturegli said many organizations seem to have missed that memo and taken things backwards – setting up their internal Active Directory framework around a user-friendly domain. local ad.

Caturegli said he knew this because he “protected himself” by registering local.ad, which he said is currently used by many large organizations to set up Active Directory – including European mobile providers, and The city of Newcastle in the United Kingdom.

ONE WPAD TO RULE THEM ALL

Caturegli said he has now registered more domains ending in .ad, such as internal.ad and schema.ad. But perhaps the most dangerous domain in his stable wpad.ad. WPAD stands for Web Proxy Auto-Discovery Protocol, which is a classic, automatic feature built into all versions of Microsoft Windows designed to make it easy for Windows computers to automatically discover and download any proxy settings required by a site. the network.

The problem is, any organization that chose a non-own .ad domain in the Active Directory setup will have a bunch of Microsoft systems constantly trying to access wpad.ad if those machines have automatic proxy discovery enabled.

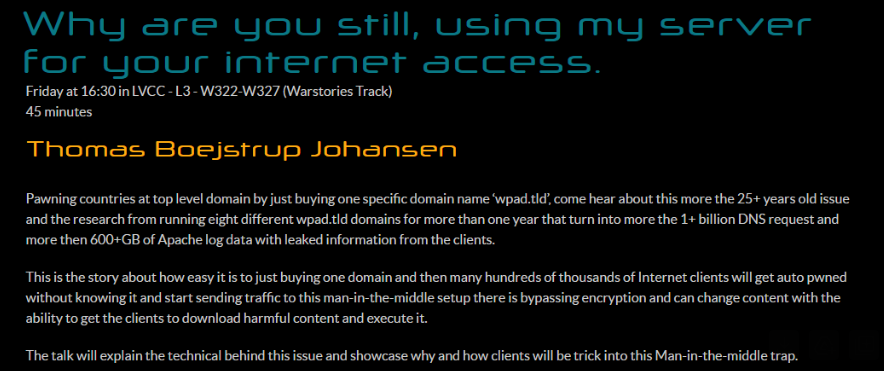

Security researchers have been bashing WPAD for more than two decades now, repeatedly warning how it can be abused for nefarious purposes. At this year’s DEF CON security conference in Las Vegas, for example, a researcher showed what happened after registering a domain. wpad.dk: Shortly after opening the domain, they found a number of WPAD requests on Microsoft Windows systems in Denmark that had namespace conflicts in their Active Directory locations.

Photo: Defcon.org.

For his part, Caturegli has set up a server to resolve and record any internet address Microsoft Sharepoint systems trying to access wpad.ad, and saw that over one week it received more than 140,000 hits from Sharepoint hosts around the world trying to connect.

The basic problem with WPAD is the same as Active Directory: Both technologies were designed for use in closed, secure, reliable office environments, and were not designed with today’s mobile devices or workers in mind.

Perhaps the single biggest reason that organizations with potential namespace conflict issues do not fix them is that rebuilding the Active Directory infrastructure around a new domain name can be incredibly disruptive, expensive, and dangerous, while the potential threat is considered relatively low.

But Caturegli said that ransomware and other cybercriminal groups can extract large amounts of Microsoft Windows data from a few companies with little upfront investment.

“It’s an easy way to get that initial access without having to launch an actual attack,” he said. “You’re just waiting for a poorly configured workstation to connect to you and send you its information.”

If we ever learn that cybercriminal groups are using namespace collisions to launch ransomware attacks, no one can say they weren’t warned. Mike O’Connoran early domain investor who registered a select few domains like bar.com, place.com and television.com, warned loud and clear back in 2013 that pending plans to add more than 1,000 new TLDs would significantly increase the number of domain conflicts of the name. O’Connor was so concerned about this problem that he offered prizes of $50,000, $25,000 and $10,000 to researchers who could propose the best solutions to reduce it.

The background of Mr. O’Connor is the most famous corp.combecause for several decades he had watched in horror as hundreds of thousands of Microsoft PCs continued to bombard his domain with information from organizations that had set up their Active Directory environments around the corp.com domain.

It turns out that Microsoft actually used corp.com as an example of how one might set up Active Directory on other Windows NT systems. Worse, some of the traffic to corp.com was coming from Microsoft’s internal networks, indicating that some part of Microsoft’s internal infrastructure was poorly configured. When O’Connor said he was ready to sell corp.com to the highest bidder in 2020, Microsoft agreed to buy the domain for an undisclosed amount.

“I think this problem is like the city [that] they know they built water with lead pipes, or the vendors of those projects knew but didn’t tell their customers,” O’Connor told KrebsOnSecurity. “This is not something random like Y2K where everyone was surprised by what happened. People knew and didn’t care.”

Source link