This is Naked Capitalism fundraising week. 146 donors have invested in our efforts to fight corruption and misconduct, especially in the financial sector. Please join us and participate through our donation page, which shows how to donate by check, credit card, debit card, PayPal. Clover, or Wise. Learn about why we’re doing this fundraising, what we’ve accomplished over the past year, and our current goal, to strengthen our IT infrastructure.

Lambert here: I always play with the slogan “The only real market is the labor market.” Maybe so….

By Wolf Richter, editor of Wolf Street. Originally published in Wolf Street.

Fewer layoffs and historically low layoffs and layoffs mean fewer job openings, and less hiring to fill them. The outbreak of the epidemic was slow. But that’s only part of it.

Unadjusted for seasonality, the number of job openings in July fell by 720,000 to 8.34 million, according to data released today by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Job openings often jump in July: Last year, they jumped by 750,000; in July 2019, they jumped by only 250,000; in July 2018, they jumped by only 414,000. So the jump in July this year was very large compared to the previous two years of the prepandemic (blue line in the chart below).

But seasonally adjusted seasonally adjusted job openings reduced seasonally adjusted job openings by 668,000 to 7.67 million (red). The entry shows data back to April 2023.

Beyond the month-to-month seasonality, we can see a trend: Job openings have declined since the labor shortage period but remain above pre-pandemic levels in data going back to 2001. So are job openings now normal? What is even normal? We’ll look at those questions in a moment.

The data is based on a survey of nearly 21,000 workplaces, released today by the BLS as part of the Job Openings and Labor Return Survey (JOLTS).

What is Normal?

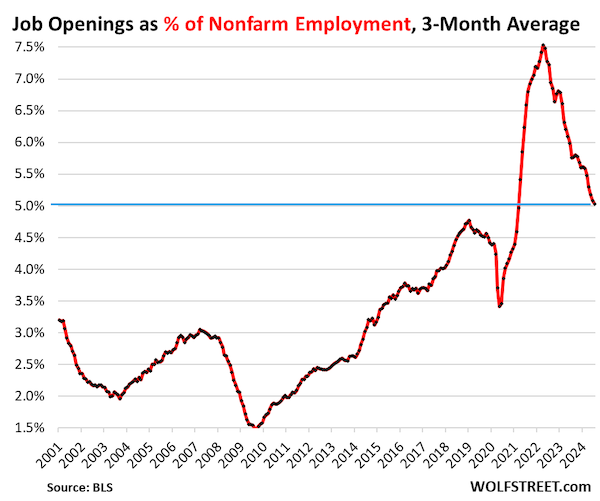

A measure of job openings and non-farm employment looks at job growth over the years. As the population, workforce, and employment grow over the years, job openings should grow as well. A measure of job openings and non-farm employment reflects this relationship.

On a seasonally adjusted basis, job openings as a percentage of farm employment fell to 4.9%, which is higher than the highest point during the strong labor market in late 2018, and the highest at any time going back to 2001.

The three-month average, which strips out some of the monthly squiggles, fell to 5.0%, above all pre-pandemic levels. This view shows that the labor shortage is over, but the labor market remains tight compared to the pandemic norm:

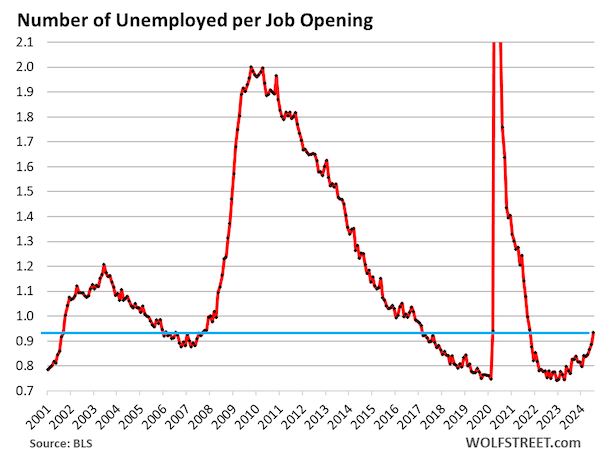

Number of unemployed people per job opening a ratio that Powell talks about a lot in his press conferences as one of the indicators of the tightness of the labor market, which means the supply of workers in relation to jobs.

The unemployed population includes the portion of the more than 6 million immigrants arriving in the US in 2022 to 2024 (Congressional Budget Office data) who are looking for work but have not yet found a job, and are therefore counted as unemployed.

This massive influx of immigrants has caused the unemployment rate to rise even though layoffs and deportations remain historically low, as we will see shortly.

In the July jobs report, there were 7.16 million unemployed job seekers, while in today’s JOLTS data, there were 7.67 million job openings in July (both seasonally adjusted), so 0.93 unemployed job seekers for each job opening.

From this point of view, which includes a large number of immigrants still looking for work, the labor market is looser (greater availability of workers) than it was during the labor market that was strong in 2018 and 2019:

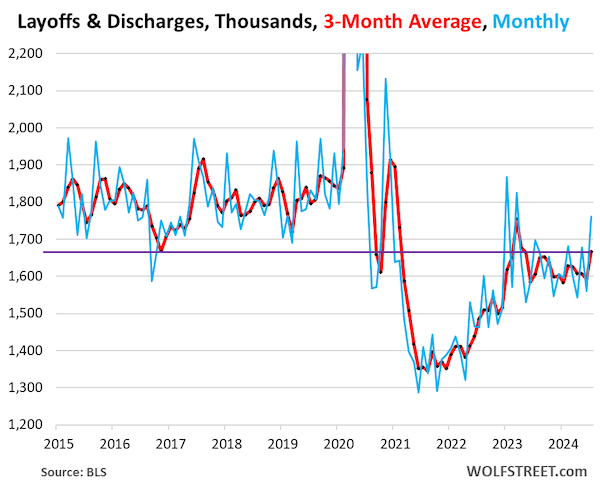

Layoffs and evictions jumped to 1.76 million in July after falling sharply in June. This is highly variable data with large month-to-month squiggles. The three-month average brings out some squiggles. It rose to 1.67 million, still in the same range it has been since early 2023, and below the low point of the pre-pandemic years.

Initial unemployment insurance claims reported by the Department of Labor showed a similar pattern: Despite some breathless headlines about layoff announcements around the world, there were fewer layoffs and layoffs than during the Good Times before the pandemic.

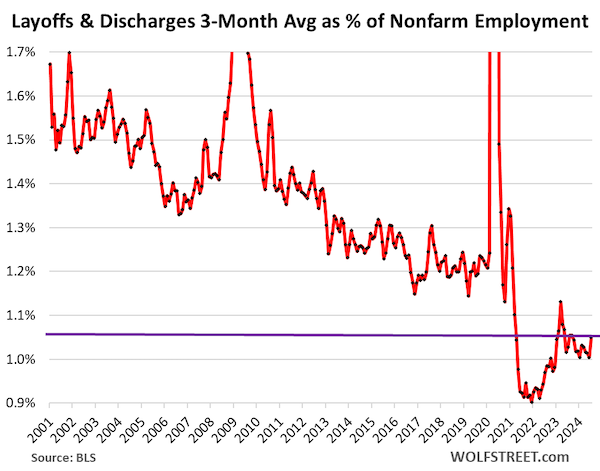

Layoffs and layoffs related to non-farm employment a ratio that accounts for job growth over the years.

From that perspective, layoffs and layoffs are still well below normal (to rule out some of the larger month-to-month issues, we use a three-month average of layoffs and layoffs).

This is a sign that employers are committed to their employees. Some economists have thought that employers “hire” workers because they are suffering from a shortage of workers after they were laid off in large numbers during the violence when they could not hire people they would let go. If true, that would be a good thing. Maybe employers have learned something.

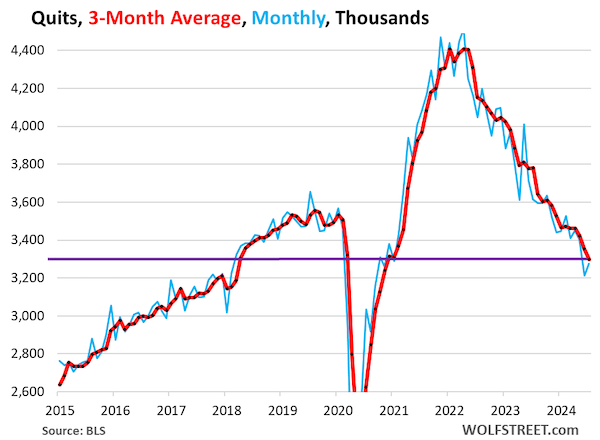

And the workers stopped quitting. Voluntary resignations reached 3.28 million in July. The three-month average fell to 3.30 million, below 2018 and 2019 levels.

After the great upheaval during the pandemic, when workers jumped jobs and industries to improve their wages and working conditions, they seem to have stabilized.

Fewer voluntary layoffs and historically low layoffs and layoffs mean fewer job openings to fill, which means less hiring, and less competition for labor. The great chaos during the pandemic is over, that’s for sure.

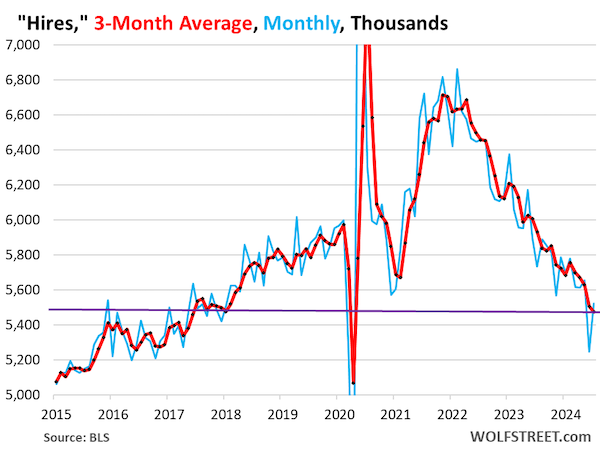

The rent is over to 5.52 million in July, seasonally adjusted, after declining in June. The three-month average fell to 5.47 million.

So let’s repeat: Fewer voluntary layoffs and historically low layoffs and layoffs — as employers stick with their workers — means fewer job openings to fill, which means less hiring. And that’s part of what we’re seeing here.

The other part we’re seeing here is that the economy is now creating jobs at a lower rate than in the heady days of 2022 and 2023, and there are fewer new jobs to be filled.

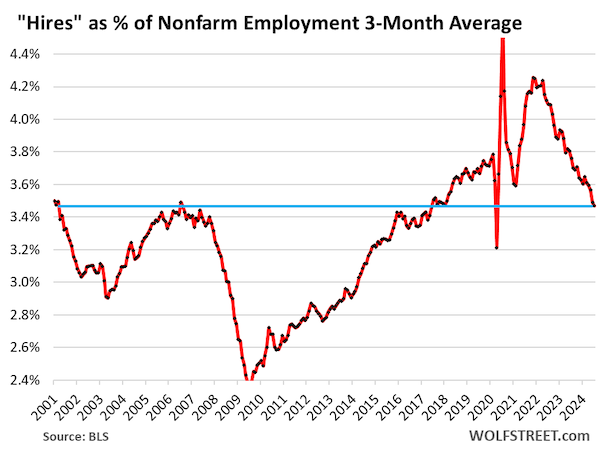

Hires in relation to nonfarm payrolls fell below 2018-2019 levels, which were considered strong labor market conditions, but remained above all months in the past dating back to 2001. Is this level of hiring relative to payrolls historically “normal?” It is possible.

Source link