Today’s article on whether it matters if a dis-inversion occurs because short prices fall, or long prices rise.

Two years ago, an inversion of the yield curve—short-term Treasuries yielding more than long-term bonds—was taken by investors as a sure sign of a recession. Now Wall Street worries have a new concern: The yield curve has returned to normal, a sure sign of recession.

Here’s a breakdown of the 10-year to two-term (2s10) change from early June:

Figure 1: The change from 1 June 2024 in the 10-year to two-year spread (bold black), the contribution to the change from the 10-year yield (blue bars), from the 2-year yield (tan), all in percent. Source: Treasury via FRED, and author’s calculations.

Indeed, slightly more than half of the increase is associated with short-term declines. If we compare it to the recession of 2008, we see a similar pattern.

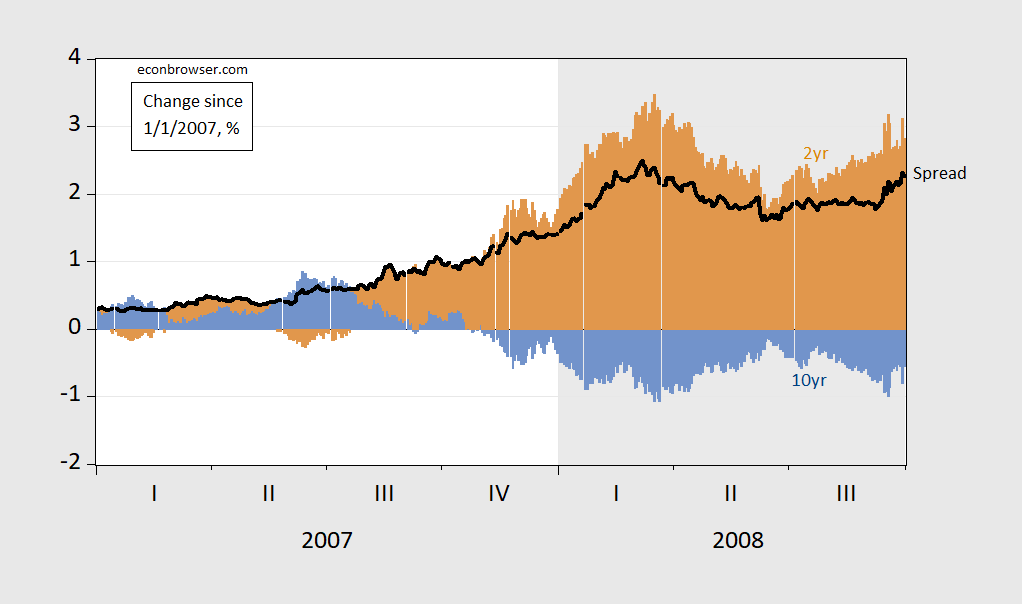

Figure 2: The change since 1 January 2007 in the 10-year to two-year spread (bold black), the contribution to the change from the 10-year yield (blue bars), from the 2-year yield (tan), all in percentages. Source: Treasury via FRED, and author’s calculations.

The overwhelming majority of bankruptcies have been due to 2-year yield declines (ie, the “bear boom”).

What about the 2001 recession?

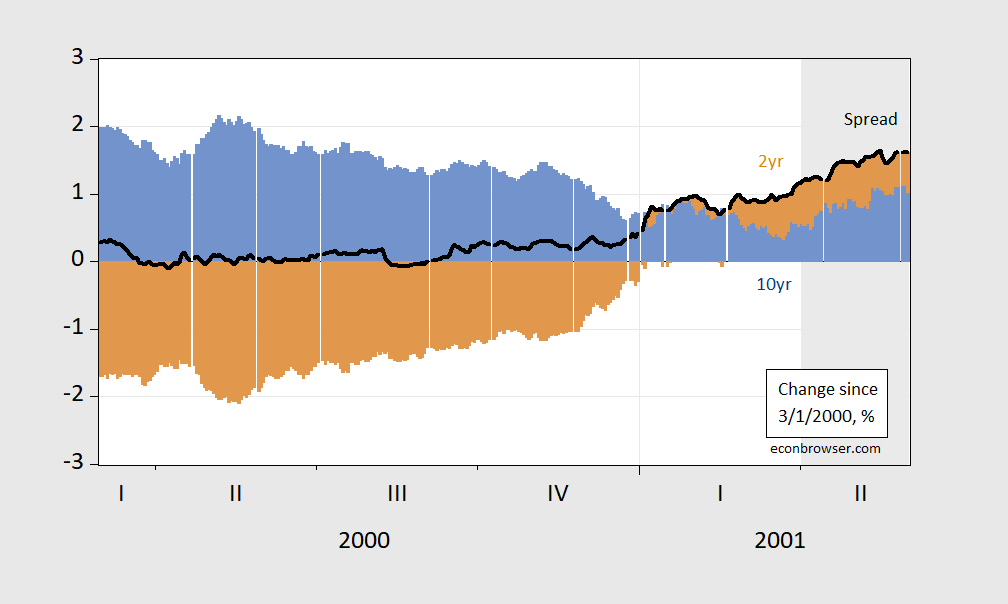

Figure 3: Change since March 1, 2000, in 10-year to two-term spreads (bold black), contribution to change from 10-year yield (blue bars), from 2-year yield (tan), all in percentages. Source: Treasury via FRED, and author’s calculations.

Here, we may call it a “bear rise”, where most of the name of the increase in the spread was due to a long rising rate, until just before the beginning of the recession, which was in April 2001 (as the NBER puts the peak in March 2001).

So, none of this is to discount the possibility of an early recession – just that one cannot really make a judgment based on whether short rates are falling, or long rates are rising.

Source link