Today we are pleased to present a guest contribution by Jamel Saadaoui (University Paris 8).

Recent literature suggests that climate risk reduces the financial environment, see Beirne et al. (2021) for example. The reason is straightforward and easy to understand. Financial markets will price the impact of climate risk in the form of higher bond yields and lower long-term foreign currency debt ratings. This weather risk premium it will have a significant negative impact on the financing of green transitions, especially in emerging markets. However, the literature has not examined the role of financial development and political stability in climate risk financing. Intuitively, it seems logical to think that countries with better financial systems and a more stable political environment will face less pressure on their financial environment. In a recent paper with John Beirne, Donghyun Park, Jamel Saadaoui, and Gazi Salah Uddin, we investigate this issue. With a sample of 199 economies for 1990-2022, we first confirm that climate risk negatively affects the financial environment. We find that such effects are most pronounced in economies most vulnerable to climate change. However, our evidence shows that political stability and financial development can reduce such effects. We also identify nonlinearities in the local climate risk nexus. More specifically, the impact of climate risk on the financial environment is greater when the financial environment is more entrenched, that is, at a higher level of distribution.

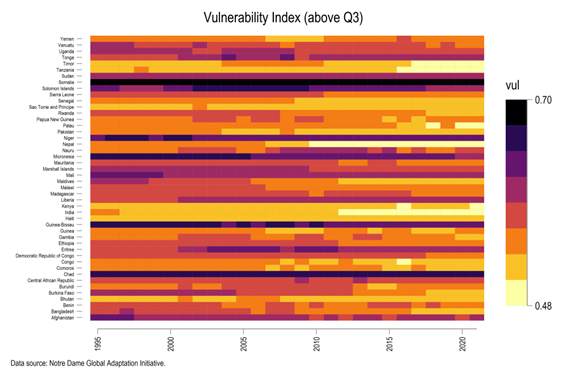

Figure 1. Low impact heat build.

To measure climate vulnerability, we use ND-GAIN Vulnerability scores. These points are artificial steps forward for vulnerability to climate change. In Figures 1 and 2, we can see that countries located in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia are the most vulnerable to climate risks. Along with the presence of the most developed countries in Figure 1, we find several countries that do not belong to the group of most advanced economies in terms of economic development. These countries have low vulnerability scores (ie, high resilience to climate risks) due to very good scores in other ND-GAIN sub-categories of the overall vulnerability score, such as infrastructure quality or energy independence sub-categories.

Figure 2. The temperature structure of the effect of high vulnerability.

In Figure 2, we can notice that the countries are at high risk (more than three quarters). These countries tend to be at low levels of economic and institutional development. These countries tend to have less developed domestic capital markets. Relative to the group of countries presented in Figure 1, this group of countries is very similar. We find countries in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. In these countries, paved roads, electricity and reliable drinking water remain scarce. For example, Chad and Afghanistan have very high vulnerability scores for both agricultural capacity and medical workforce provision.

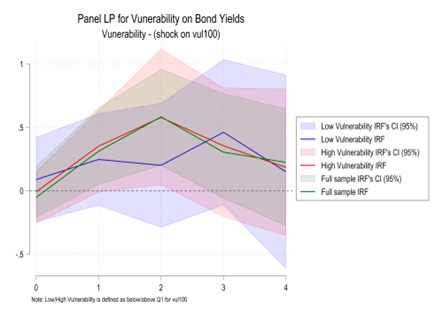

In Figure 3, we use the Local Panel projection and a list of local and global controls in accordance with the documentation. Our baseline case across countries shows a statistically significant premium in sovereign bond yields due to exposure to climate risk, reflecting the net return investors seek by holding that debt. Further, we divided the sample between low and high climate vulnerability, depending on the value of the vulnerability score. In countries with less climate risk, a statistically significant effect is not found. This is consistent with economic intuition, that is, low levels of climate exposure will not lead to climate-related premia in sovereign bonds. For countries most exposed to climate change, the impact on bond yields is significant, as expected. Interestingly, the result is broadly consistent with that of the panel as a whole in terms of magnitude, suggesting that countries most vulnerable to climate change may have overall effects.

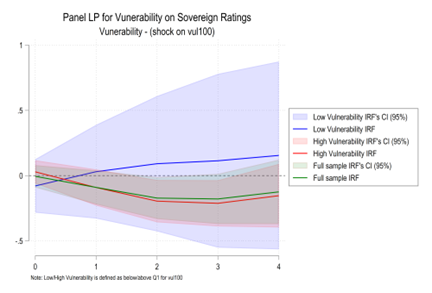

In Figure 4, we perform the same basic analysis of independent measures, our second measure of financial space. We find a consistent effect on bond yields, where a shock to climate vulnerability will lead to a steady decline in the sovereign ratings of the full sample and countries with high climate vulnerability. In less vulnerable countries, we do not see such a sustained deterioration in sovereign ratings, as expected.

Figure 3. LP panel for the impact of risk on bond yields.

Figure 4. LP panel for the impact of vulnerability on independent estimates.

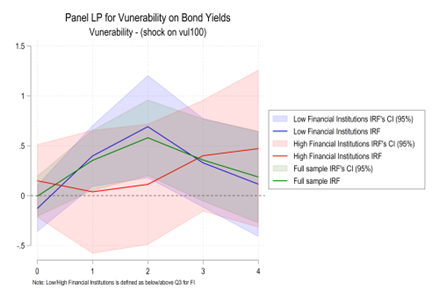

In Figure 5, we use the Financial Institution Development Index (Svirydzenka, 2016) to investigate the impact of financial institution development on the impact of risk shocks on the financial space. In countries with mature financial institutions, shocks to climate risk do not cause bond yields to rise.

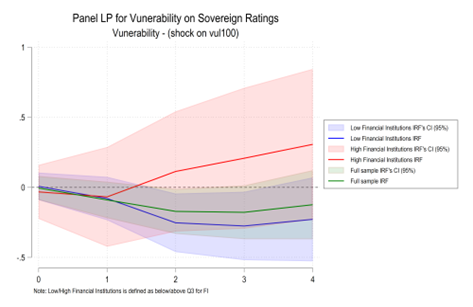

In Figure 6, we can see that climate vulnerability shocks do not have a significant impact on the sovereign ratings of countries with high levels of financial institution development. On the other hand, the climate vulnerability shock causes a continuous deterioration in the sovereign ratings of countries with low financial institutions and the full sample, which causes the importance of sound financial institutions. The dampening effect of improved financial development on the climate-finance nexus follows intuition, where there is greater depth and funds in local financial markets and insurance markets are better developed.

Figure 5. LP panel on the impact of risk on bond yields (Financial Institutions)

Figure 6. LP panel on the impact of risk on sovereign ratings (Financial Institutions)

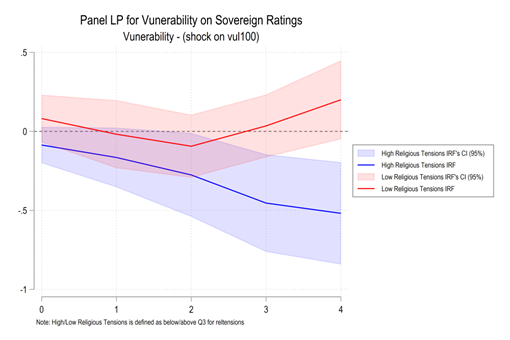

Our result, using ICRG data (PRS group), confirms our main understanding of several dimensions of political stability (External Conflict, Internal Conflict, Government Stability, Ethnic Conflict). Countries with stable political systems have experienced the least amount of climate risk. Notably, the climate risk premium remains constant in only one area of political stability, namely religious tension. These results may help policy makers to understand the role of political stability and financial development in financing environmental change.

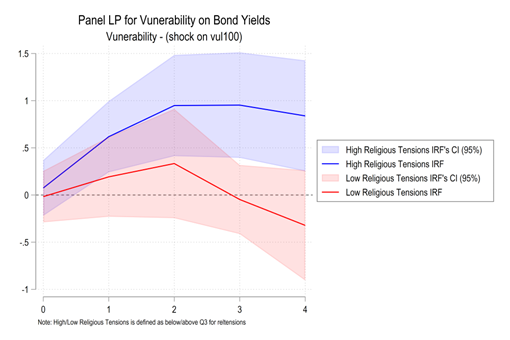

Figure 7. LP panel on the impact of vulnerability on bond products (Religious Conflicts)

Figure 8. LP panel on the impact of vulnerability on independent standards (Religious Conflicts)

This post was written by Jamel Saadaoui.

Source link