Tyler Cowen was recently linked lesson that suggests that society does not believe in supply and demand, at least when it comes to the housing market:

Recent research finds that many people want lower house prices but, contrary to the consensus of experts, do not believe that more supply will lower prices.

Before talking about housing, it is important to note that the same kind of desperation is growing in many other situations. And as we’ll see, it’s a mistake to view this pessimism as a denial of the supply and demand model—which is something else going on.

Consider the following two situations, presented to the average person:

A. The company is facing a very high cost of a key ingredient in its product.

B. The company benefits from the lowest cost of its product’s key ingredient.

In each case, what is the firm likely to do? In economics, nothing can be easy. Our models are equal. A profit-maximizing firm will have an incentive to raise prices in case A, and lower prices in case B. (BTW, the theory predicts these results even if the firm is a single entity.)

During my life, I have discovered that this is not the way ordinary people look at things. It’s not a question of supply and demand, they have it asymmetric pessimism. What are the causes of this pessimism?

1. Perhaps asymmetric pessimism is true. Perhaps firms would indeed raise prices in case A, but not cut them in case B. In any meaningful long-term sense this is not the case. But it’s unlikely that consumers may notice a few real-world examples of prices that can be cut right away, due to the so-called “price stickiness”.

2. In a normal inflationary situation, people may be more likely to notice rising prices than falling prices. Economists are interested in this relative valuesbut the common man looks at the prices. If a company raises prices by 2% in a year of 4% CPI inflation, that is a price cut for the economy and a price increase for the average person.

3. Maybe people are reluctant to sound ignorant, or pollyannish. I am not the first person to realize that pessimism is a much smarter fashion than optimism. People like Stephen Pinker are considered notable dissidents for identifying a number of positive trends that every educated person should know about. Is the world getting richer, healthier and safer? What else is new? But it is clear that he has become a controversy.

4. The media often report bad news. So what should a voter think when asked whether some new government policy can fix a long-standing problem? Do they expect next year to wake up in the press reporting that our economic problems have been solved and that housing is now “affordable”?

5. Balancing greed and high prices. In fact, firms that reduce prices after falling input prices they are “greedy”. But most people probably think that the profit-maximizing option in that situation is not to cut prices. Because they have already decided that firms are greedy, they then think back to the conclusion that prices will not be lowered.

I suspect that people believe that the laws of supply and demand apply to the housing market. Ask them what will happen to rental housing if a flood of immigrants pours into their town. I suspect they are answering a different question than what the economist thought he was asking. An appraiser might think that he is asking, “Other things being equal, what is the maximum value of the housing offer?” The public may respond as if they were being asked “If this regulatory change happened, would I expect apartment rents to be lower a year from today?”

In my opinion, these poll questions are useless. Instead, imagine a world where one political party opposes the building of more housing and the other political party favors greater pressure to increase the supply of new housing. And let’s say that these policy ideas are widely known among the public. Now ask a young voter about to graduate from college which organization would make housing more affordable.

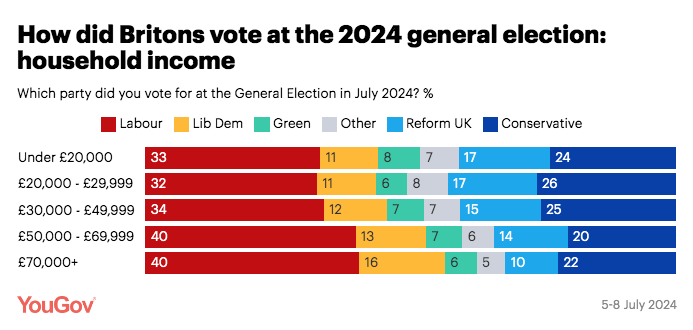

We don’t need to speculate on that question. A few months ago the British Conservatives campaigned on a certain Nimby base, while Labor ran on a strong Nimby base. Check it out this study since the last election:

You might think that this pattern is due to rich people voting Conservative. But it’s not that simple:

In fairness, half of Conservative voters were low-income retirees, who may have been very wealthy when they were young.

Source link