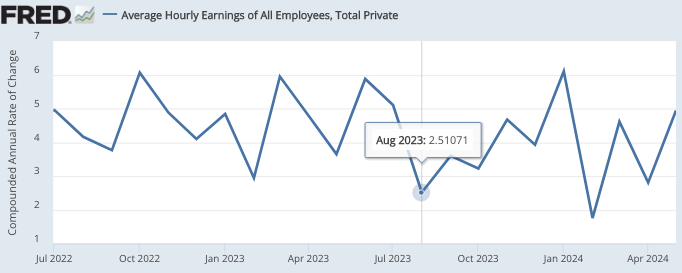

Today’s jobs report contained two pieces of information that suggest policy may be more expansionary. First, payroll employment rose more strongly than expected to 272,000. (The household survey was weak, but that data is considered less reliable.) Second, nominal wages grew by 0.4% (an annual average of about 5%). tilt things towards the idea that the policy is too flexible. That doesn’t mean we can be sure that the policy is too broad, that this claim is now more likely to be true.

The 10-year T-bond market reacted with a selloff, meaning long-term interest rates rose:

Markets are currently expecting a rate cut by the Fed later this year. This may happen because inflation is falling, or because the real economy is in danger of collapsing. Today’s news has made both of those outcomes seem less likely. Wage inflation has reached 4.1% over the past 12 months, a rate that is inconsistent with the Fed’s “price stability” goals, even if you define price stability as 2% inflation. Over time, wage inflation tends to run about 1% to 1.5% above inflation. Unfortunately, progress in reducing wage inflation appears to have stalled over the past 10 months. The next two or three readings will be very important.

I don’t have strong views on where the Fed should set its interest rate target at this point. I have strong views on past monetary policy, which has been very tight over the last three years. The longer these policy transitions continue, the stronger the transition to a policy-oriented approach, where the Fed will commit to correcting previous policy mistakes. I thought they intended to do that back in 2020, but it turns out that “targeted rate of inflation” was not an accurate description of their new policy.

This post is titled “double trouble”, although the number of paid employees can be considered good news. These statistics are a problem for the Fed which seems to be hoping that it will soon be able to lower the interest rate target. In my opinion, it’s a mistake for the central bank to take action on low interest rates, just as it was a mistake for the Fed to choose higher interest rates back in 2015. They should not choose low or high interest rates; they should favor macroeconomic stability (in general). Let the market decide what kind of interest rates are compatible with maximum stability.

PS. This comment on FT catch my eye:

Jason Furman, a former economist who is now at Harvard University, said the increase in unemployment could be the most important part of Friday’s data release.

“If we wake up next month, the unemployment rate is 4.1 percent, I think it will get.” [the Fed’s] attention,” said Furman. “If you have more than 4 jobs, that can reduce the level of play early on.”

In the 1970s, the Fed thought that a rising unemployment rate was a sign that money was too tight. It wasn’t like that. The Fed should never target the unemployment rate, since no one knows exactly what the natural rate of unemployment is at any point in time. The Fed should target the standard deviation, nominal GDP. It is generally true that rising unemployment is a sign that easy money is needed, but not when NGDP is growing by 5%.

Source link