That’s the headline of a Timiraos/WSJ article three days ago:

Often in a recession recovery, households are more careful with spending and are more likely to save. When rates are low, borrowing supports spending. Higher prices choke off that consumption.

In this case, economic activity is based more on wealth and income than on credit. The pandemic changed spending habits, combined with higher commodity prices, tighter job opportunities and government incentives, leaving many households feeling shell-shocked.

As I have noted in previous indicators of the business cycle recalculation in May/April, the answer to the above question can be: (1) the recession is already there and we do not see it in the preliminary data, (2) the recession is coming, since the time between the spread of the term and the beginning of the recession varies, (3) the model the one we used is wrong, (4) it’s just luck of the draw (previous estimates based on short samples have not shown 100% probabilities, eg here).

Here is an updated assessment of the likelihood of a recession (next 12 months), which includes data through May 2024, and assumes no recession has occurred since June 2024.

Figure 1: Estimated economic recession for the next 12 months, using the 10yr-3mo spread and 3-month average (blue), the 10-3mo spread, the 3-mo average, and the non-financial private sector debt service ratio ( tan), and the 10-3mo spread, the 3mo average, the non-financial private sector debt service ratio, and the foreign currency spread (green). Measurement sample 1985M03-2024M06. The NBER has defined recession days as shaded in gray. Source: Author’s calculations, and NBER.

Note that the foreign word spreads improved specification (Ahmed-Chinn definition stripped of oil prices, equity return/volatility, and financial condition index, supplemented by debt service ratio) peaking at 41% in May. The improved DSR specification (following Chinn-Ferrara, which omits the financial conditions index) produces a higher probability of a 24% recession in May 2024. This latest specification incorporates the concept of strong consumer balance sheets, and the inclusion of home-owner mortgages in mortgage rates, to the rate at which the debt service ratio remains relatively low.

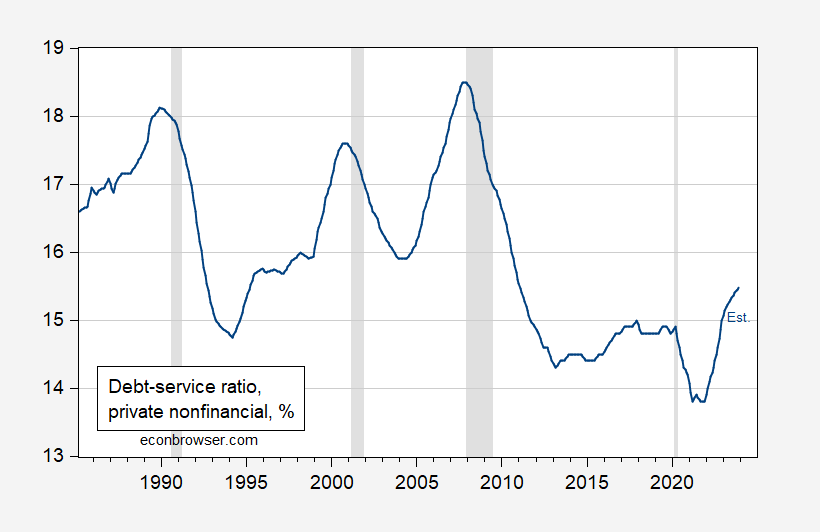

Figure 2: Non-financial private sector debt service ratios, % (blue). 2023Q4 is estimated using interest rates (see here). The NBER has defined recession days as shaded in gray. Source: BIS, Dora Fan Xia, NBER, and author’s calculations.

The highest estimated probability is May 2024; we only have employment data for May (usually monthly).

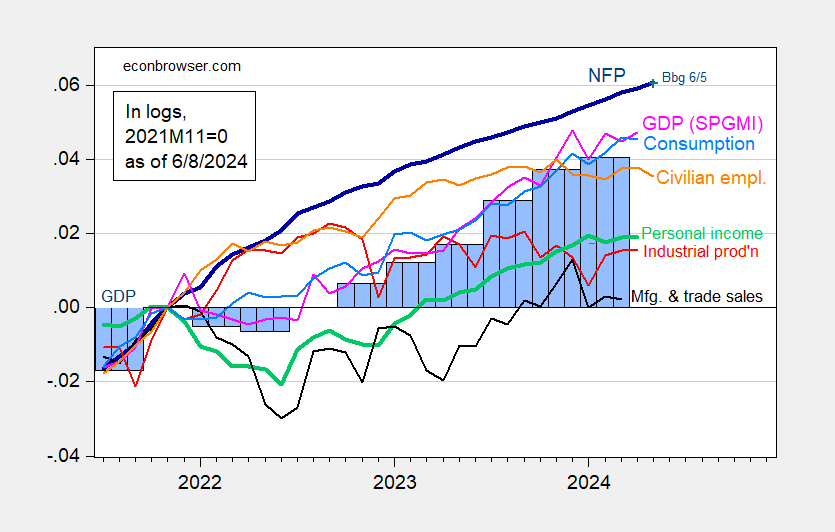

Figure 3: Nonfarm Payroll (NFP) from CES (blue), employment (orange), industrial production (red), personal income excluding current transfers in Ch.2017$ (bright green), trade and sales in Ch.2017$ (black), consumption in Ch.2017$ (blue), and monthly GDP in Ch.2017$ (pink), GDP (green bars), all log normalized to to 2021M11=0. Source: BLS via FRED, Federal Reserve, BEA 2024Q1 second release, S&P Global Market Insights (with Macroeconomic Advisers, IHS Markit) (6/1/2024), and author’s calculations.

And some reliable indicators suggest a slightly stronger growth, at least until the end of 2023.

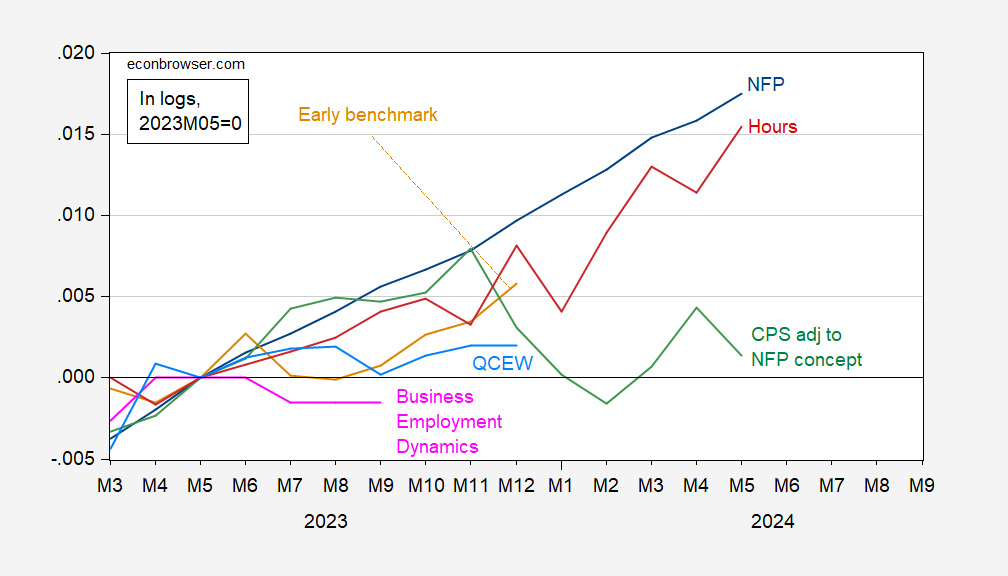

Figure 4: Nonfarm payroll employment (blue), preliminary benchmark, calculated by adjusting the actual consumption ratio for the prior benchmark total for the total of CES states (tan), the CPS ratio adjusted for the NFP assumption (green), the total QCEW covered labor seasonally adjusted by the author using the geometric moving average (blue), Business Employment Dynamics cumulative growth in 2019Q4 NFP (pink), and aggregate hours (red), all in logs, 2023M05=0. Source: BLS, Philadelphia Fed, and author’s statistics.

Source link