An abstract from a forthcoming article in Journal of International Money and Finance.

We begin by examining measures of aggregate foreign exchange holdings held by central banks (the size of the issuing country’s economy and capital markets, the currency’s ability to hold value, and inertia). But understanding the determination of reserves probably requires going beyond aggregate numbers, looking instead at the behavior of each central bank, including host country characteristics (bilateral trade with the issuing country, the bilateral currency peg, and proxies for bilateral sanctions exposure), in addition to issuer characteristics of the reserve. On a currency-by-currency basis, the holdings of the US dollar are somewhat better explained by several factors of extraction; but some funds are not effectively defined. It is possible that the results from the currency-to-currency comparison are distorted by an insufficient sample size. This consideration provides an incentive to aggregate data across major currencies and to impose restrictions on whether holdings are determined in the same way for each currency. In this setting, many economic determinants come into play: the size of the economy as measured by GDP, the bilateral currency peg, and the bilateral trade share. While one geopolitical factor (consistency in UN voting) is more significant than expected (except for the US dollar), the other geopolitical factor (sanctions) does not enter into significance.

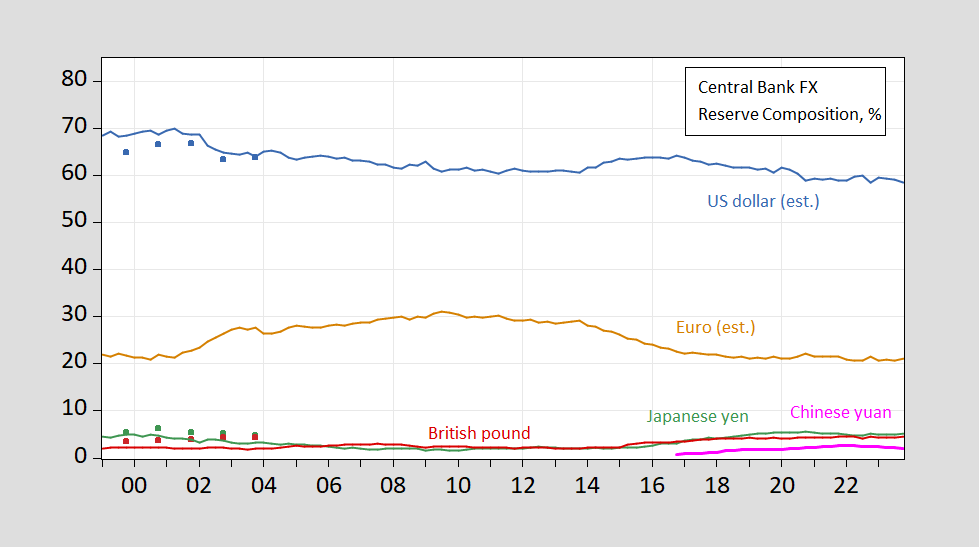

Here’s a picture of aggregated currency shares, from the IMF’s COFER database, updated data released on June 11.

Figure 1: Share of foreign exchange reserves held by central banks, in USD (blue), EUR (orange), DEM (tan squares), JPY (green), GBP (sky blue), Swiss francs (purple), CNY (red). For information from 1999 onwards, estimates based on COFER data, and allocation of unallocated reserves, are described in the text. Source: Chinn and Frankel (2007), IMF COFER accessed 6/20/2024, and author’s estimates.

And here are the details, from 1999 onwards:

Figure 2: Share of foreign exchange funds held by central banks, in USD (blue), EUR (orange), JPY (green), GBP (sky blue), Swiss francs (purple), CNY (in red). For information from 1999 onwards, estimates based on COFER data, and the allocation of unallocated reserves, are described in the text. Source: Chinn and Frankel (2007), IMF COFER accessed 6/20/2024, and author’s estimates.

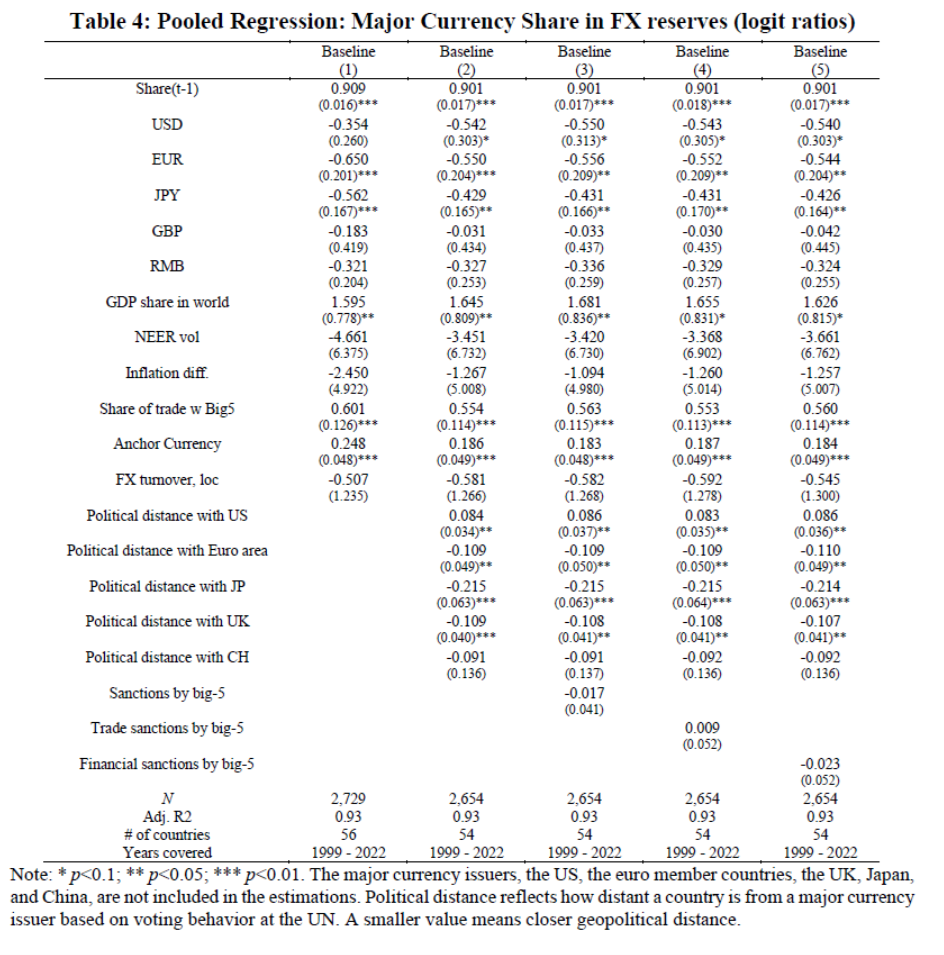

The calculations used to estimate the combined shares before EMU are of no use in predicting the shares now. Therefore, in this new paper, we rely on data from each major bank to estimate stock characteristics. The results for the combined currency of various countries, which restrict the country distance coefficient to vary across currencies, are reported in Table 4.

Source: Chinn, Frankel, Ito (forthcoming, JIMF).

Following the results in Chinn and Frankel (2007), we find issues of economic size, and inertia. Although we find measures of retail price (inflation, exchange rate volatility) have negative effects, those effects are not statistically significant. This special data set (annual central bank) allows us to investigate the impact of trade flows and the peg, which turns out to be significant. We replicate the findings of Goldberg and Hannaoui (2024). More Geographically distant countries (as measured by consensus in UN GA voting) have larger shares of dollars, while the opposite is true for other currencies. Although financial sanctions have a negative effect, the relative sensitivity is not statistically significant.

Although we do not clearly record how dollar stocks have fallen, it is useful to note that some studies (see Arslanalp, Eichengreen and Simpson-Bell (2024), and references therein) have documented that the slack is rarely captured. in RMB, but other unusual currencies.

See also Eswar Prasad’s recent Foreign Affairs section, Third annual Fed-FRBNY Conference on the international roles of the dollar, Kamin and Sobel (2024), Atlantic Council “Dollar Dominance Monitor”.

Source link