Today we are pleased to present a guest contribution written by Christopher A. Hartwell (ZHAW School of Management and Law, Switzerland), and Pierre Siklos (Professor Emeritus at Wilfrid Laurier University; and Balsillie School of International Affairs, Canada).

Our mutual paper, from International Journal of Central Banking, makes the case that inefficient central banks – in particular, those that consistently miss their inflation targets – not only undermine their credibility, but also undermine the quality of a country’s institutions. So, when you ask: What Damage Can an Inefficient Central Bank Do? The answer is: a lot, actually. Such a conclusion has far-reaching consequences for institutional development, leading to a reduction in overall economic stability.

Since the policy of central bank independence spread throughout the world, financial authorities have played, some would say, a major role in determining the direction of the country’s economy. Given this importance, we think that the way a central bank works can have a major impact not only on the performance of the economy but on the strength of its institutions. For example, a short-term decrease in the central bank’s credibility, the volatility of the flow, means a similar decrease in all. to trust placed in central banks, with variable trusts such as slow stocks. If this trust begins to erode in the central bank, there is the potential to undermine the reputation of the country’s institutions more broadly. Weak institutions translate into less institutional strength in the economy. We think of resilience as a country’s ability to withstand shocks, which can be both economic and political.

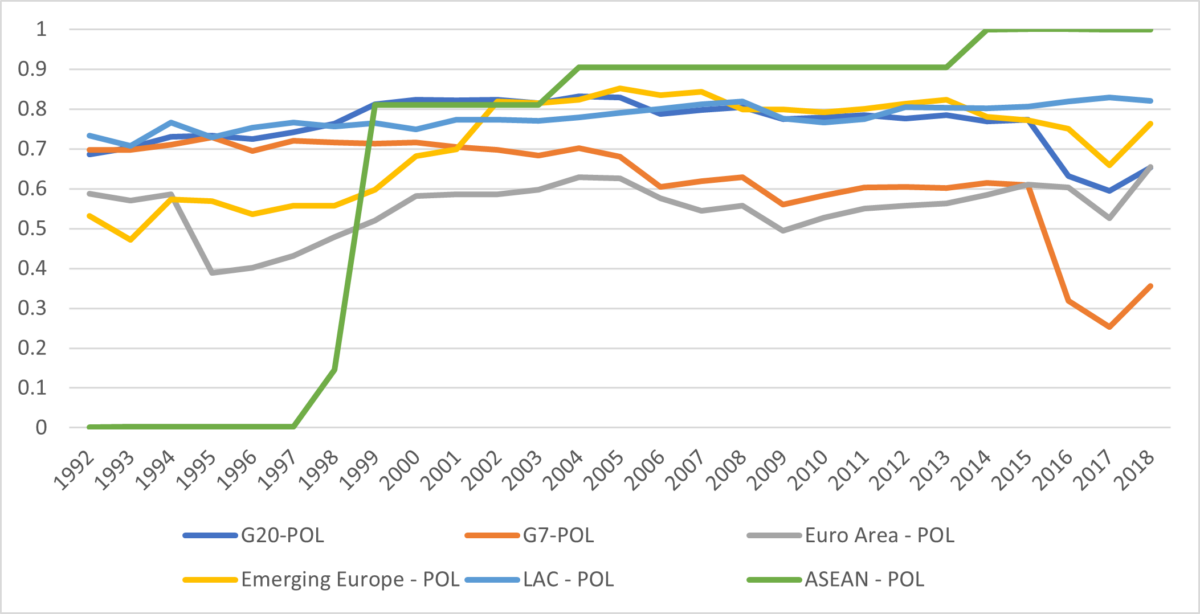

To measure this relationship, we construct an index of institutional strength that includes economic (eg, scope of property rights, degree of trade and financial openness, and exchange rate volatility) and political (eg, democracy, administrative boundaries, and size of government finances). This indicator captures factors that should be positively related to resilience, except for government size, which should be negatively related (larger government has less room for maneuver in the face of shocks). The graphs below show our findings about economic and political stability (the index ranges from 0 to 1) for selected country groups, although we have made these indicators for each of the more than 90 countries in our data set (representing more than 80% of the world’s GDP). While our data goes back to the 1960s, it is only in the 1990s that a more comprehensive list of variables considered is consistently available in countries beyond developed economies. As shown below, the 1990s and 2000s saw a global increase in central bank strengthening although there is considerable variation over time and the gaps between the country groups shown show few signs of convergence at the end of the sample in the early 1990s. Gaps in political stability remain throughout the sample analyzed and there is a significant decline in G7 countries from 2015 preceding the pandemic and recent events. The G7 was among the most politically resistant countries in the early 1990s.

Figure 1: Economic Stability. Higher scores mean greater resilience

Figure 2: Political Stability. Higher scores mean greater resilience

We plot this index against a measure of central bank efficiency, which is grouped according to three different components. First, we compare the central bank’s inflation performance against stated targets – in the case of monetary policy – or against an implicit target (a five-year moving average of inflation outcomes) – where banks do not have a pre-specified target. Second, we measure monetary policy uncertainty, measuring the variance of inflation and output relative to forecasts. Finally, we measure how the country’s inflation performance is out of step with the rest of the world.

Using the general method of moments (GMM), model selection techniques, and local forecast estimation from VAR, we find that each percentage point decline in central bank reliability is associated with an average 3.6% decline in the stability of a country’s institution since the 1990s. Simply put, the more a central bank loses confidence by missing inflation targets or by deviating from global norms, the more it damages a country’s overall institutional stability.

The results of this study also highlight that central bank independence may lead to better inflation outcomes, but the central bank can still pursue poor or ineffective policies even when independence is controlled. A more efficient central bank, that is, one that focuses more on price stability, is better for the economy; more importantly, since central banks play such an important institutional role in the economy, the overall institutional quality of a country can depend on how well the central bank operates. Although our results depend on incomplete indicators we have tried, within the limitations of data availability, to determine the sensitivity of our results to changes in the definition, changes in sampling periods, and data sources. Our main findings remain robust across measurement methods used.

This post was written by Christopher Hartwell again Pierre Siklos.

Source link