By Alex Hollingsworth, Associate Professor at The Ohio State University, Krzysztof Karbownik, Assistant Professor, Department of Economics at Emory University, Melissa A. Thomasson, Professor of Economics at the University of Miami, and Anthony Wray, and Associate Professor at the University Of Southern Denmark. Originally published at VoxEU.

Both black and white infant mortality rates in the US have declined over the past century, but the racial disparity in infant mortality is worse. This column studies the impact of major hospital modernization programs in the 20th century on health care capacity and mortality outcomes, with a focus on racial disparities. Improving health care lowered the infant mortality rate and narrowed the white-white infant mortality gap by one quarter. Cost-effective investments in health care infrastructure have disproportionately benefited historically underserved groups, had long-lasting benefits, and accompanied the development of new treatments rather than replacements.

Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states “[e]everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and his family, including … health care and necessary social services” (United Nations 1948). Despite this, the majority of people in the world do not receive care from doctors and hospitals. In 2017, North America had 2.7 hospital beds per 1,000 people, while South Asia had only 0.6 (WHO 2017).

Access also varies in high-income countries. The US and Switzerland have the largest health costs per capita in the world, but the US has 60% more hospital beds and doctors per 1,000 people compared to Switzerland (Papanicolas et al. 2018, WHO 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic (Propper and Kunz 2020) and the tendency to centralize health care, shortage of doctors, and inadequate funding, can reduce access, creating health deserts, especially in socially and economically disadvantaged areas. Research on the impact of reducing hospital capacity is mixed. Kozhimanil et al. (2018), Germack et al. (2019), and Gujral (2020) report the negative effects of hospital closures, while Fischer et al. (2024) do not find similar results.

In the US, these challenges persist despite dramatic changes in health care spending and population health over the past century (Cutler et al. 2019). In the last century, health care spending has increased tenfold, infant mortality has decreased by 95%, and life expectancy has increased by 45% (Costa 2015). However, these impressive benefits are not equal across ethnic groups (Muller et al. 2019). In 1916, the infant mortality rate per 1,000 live births was 184.9 for Black infants and 99.0 for White infants, yielding a ratio of 1.9 (Singh and Yu 2019). By 2021, black and white infant mortality rates had dropped to 10.6 and 4.4, respectively, but the gap had widened to an average of 2.4 (Ely and Driscoll 2023). Thus, despite a large overall reduction, the racial disparity in infant mortality is worse now than it was at the beginning of the 20th century.

Given these two facts – unequal access to health care and racial inequality in health outcomes – it is important to understand whether investment in health care infrastructure can reduce these deficiencies, especially since health care now plays an important role in today’s society, accounting for approximately 20% of the economic activity of US

A campaign to develop the Duke Endowment and its results in the field of hospitals

In a new paper (Hollingsworth et al. 2024), we study how health care infrastructure funding affects health care capacity and mortality outcomes, with a particular focus on racial inequality. Our work is based on a unique case study: a large hospital system supported by the Duke Endowment in North Carolina during the first half of the 20th century. The charity has helped hospitals expand and improve existing facilities, acquire modern medical technology, and improve their management methods. In some communities, it has also helped build new hospitals or convert existing facilities to non-profits. Although funding only began in 1927, by the end of 1942 the Endowment had distributed more than $53 million (in 2017 dollars) to the government.

The subsidy increased the number of nonprofit hospitals per 1,000 eligible children, while causing a decrease in for-profit hospitals that were not eligible (Figure 1). This effect was reflected in hospital beds: non-profit beds increased by 70.1% while for-profit beds decreased by 61.4%. This led to an overall increase in both facilities and beds. In addition, the supported communities saw a 60.2% increase in high-quality doctors per 1,000 births and a 5.5% decrease in poorly trained doctors, improving the general state of medical knowledge in the areas supported by the Endowment (Figure 1). These results persisted for more than 30 years, suggesting a permanent increase in dose.

Figure 1

Effects on Infant and Long-Term Mortality

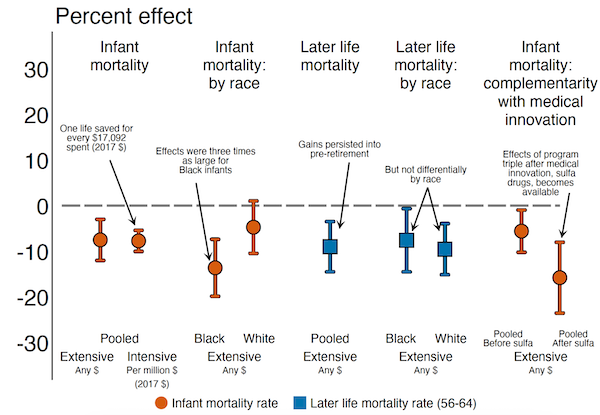

Changes in health care infrastructure help explain our core finding that Duke financial support improved health outcomes in these communities, resulting in a 7.5% reduction in infant mortality (Figure 2). The gains were nearly three times greater for Black infants (13.6%) compared to White infants (4.7%), reducing the Black-White infant mortality gap by one quarter. In addition, those exposed to support at birth also enjoyed lasting health outcomes, with long-term mortality rates (between ages 56 and 64) falling by 9.0% – a cumulative benefit similar to that of both races. These investments save money. One life was saved for every $17,092 (in 2017 dollars) paid to hospitals, a cost far lower than any reasonable estimate of the value of a statistical life.

Figure 2

Correlations Between Venture Capital and Medical Innovation

Finally, we document that Duke-supported hospitals use new medical advances more effectively, which suggests compatibility between high-quality hospitals and new medical interventions (Figure 2). We explore this by measuring the interaction between Duke’s support and the discovery of sulfa drugs in 1937, which successfully treated pneumonia. We do not see the effects of Duke funding in areas with low pneumonia mortality. On the other hand, in areas with a high baseline of pneumonia mortality, benefits exist before and after medical discovery, but the effects are almost three times greater in the post-antibiotic era. This shows the complementary nature of the modernization of the hospital with the development of medical drugs, in this case it can be explained that the Endowment attracted the most qualified doctors in the area who are better able to use new technologies.

Conclusions

We conclude that investments in health care infrastructure: (1) lead to lasting improvements in the provision and quality of health care available to affected residents; (2) providing short-term and long-term death benefits; (3) unfairly benefiting historically marginalized groups; (4) support instead of developing new treatments; and (5) they are not very expensive – at least in the case where the initial levels of health provision are low, as they are in many low-income countries today.

References are available at the beginning.

Source link