Now that we’re on the subject of recession (again), it seems like a good idea to remind ourselves of the last time some observers said outright that we’re in a recession, which was Steven Kopits, January 2, 2023:

So in H1, we were dealing with a mid-year drop in productivity, a mid-year drop in GDP, a drop in VMT, a drop in fuel consumption and 1.1 m new jobs per Establishment Survey from March to June. Those numbers are not squared. Something is wrong. Some of the numbers we might use to evaluate the Establishment Survey are inconsistent with it. That suggests the HH survey was probably close to the truth.

Now, this is not my area of expertise, let alone my area of interest. But I can look at the underlying numbers and say that some of the metrics we can examine suggest that the Est Survey was wrong.

You, Menzie, holding the Est Survey were probably right. You wrote: Therefore: (1) I put more weight on the series of invention, and (2) the gap between the two series is more likely due to increased, and biased, measurement error in the household chainrather than, for example, increasing primarily for multi-taskers.

The error died, as it turned out. And predictably so.

You were wrong because you didn’t fully consider the math. That is the point of learning for your students. Check your indicators if you have dials telling you different things. If jobs grow faster, GDP should also increase. If jobs grow rapidly, then travel and fuel consumption should increase, because more people need to drive to work in this country. Finally, if productivity increases when tasks are completed, you really need to take a moment and put together some kind of narrative as to why that is possible. It suggests some anomalies in the data that require further investigation.

If you had done that, Menzie, you would have ended up like the Philly Fed (from my earlier quote):

Response from the Philadelphia Fed:

Early Standard Marks for All 50 States and the District of Columbia

Estimates from the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia show that employment changes from March to June 2022 were significantly different in 33 states and the District of Columbia compared to current national estimates from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ (BLS) Current Employment Statistics (CES) ). Initial benchmark estimates showed high changes in four states, low changes in 29 states and the District of Columbia, and small changes in the remaining 17 states.Our estimates combine the comprehensive, accurate employment estimates released by the BLS as part of its Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW) program to supplement sample data from the BLS’ CES that are released monthly at the appropriate time. All percentage change figures are expressed as annual rates.

In total, 10,500 new jobs were added during this period instead of the 1,121,500 jobs estimated for the state total.; the US CES estimates a net increase of 1,047,000 jobs during this period.

Therefore, from March to June 2022, CES estimated 1.1 m new jobs. The Fed revised it down to 10,500.

Looks like the Philly Fed supports my ideas.

And of course, don’t we suspect that the additional 1.6 m jobs added after June by the Est Survey may be a surprise. If the HH survey proves correct again, those H2 (November) jobs gains will disappear, as will the March to June numbers.

I tried to emphasize how the data could be updated. In particular, I have noticed that many economists focus on business cycle fluctuations and place too much weight on innovation evaluations. With an additional year and a half of data, what can we see about what the data says. First, about work.

Figure 1: Non-farm payroll employment from CES (green), civilian employment from CPS (tan), population employment, adjusted for CBO estimates of immigration (blue), all in 000s, for Putative peak-to-trough recession of 2022H1 shaded lilac. Source: BLS, CBO, and author’s statistics.

Note that there have been two revisions to the CES numbers, and one preliminary benchmark from the Philadelphia Fed, since Mr. we can count on the NFP series at this time.

What about combined output?

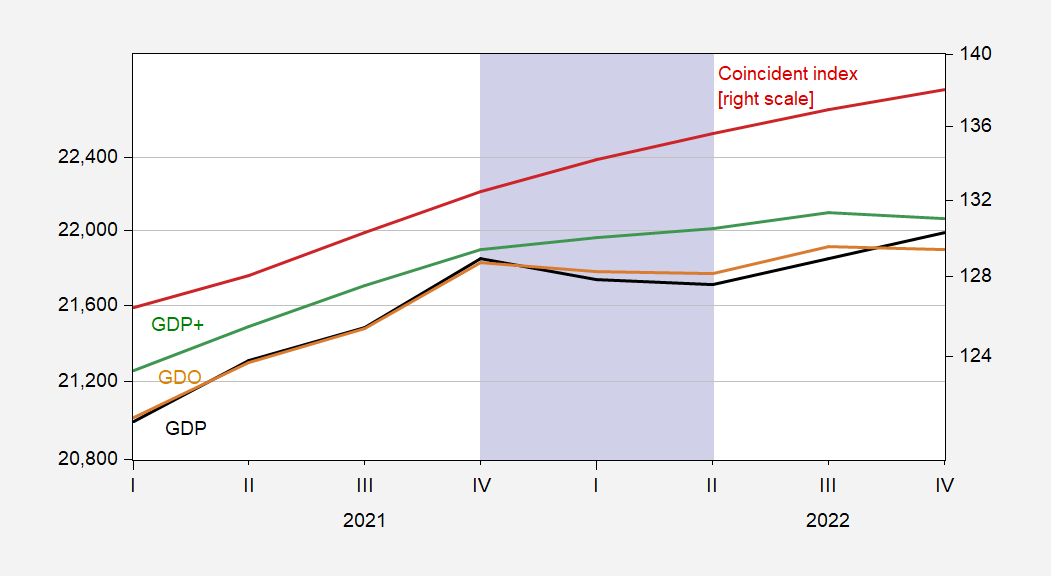

Figure 2: GDP (black scale, left scale), GDO (tan, left scale), GDP+ (green scale, left scale), all in bn.Ch.2017$ SAAR, and the corresponding index (red, right scale). Recession tolerant lilac shade 2022H1. Source: BEA via FRED, Philadelphia Fed.

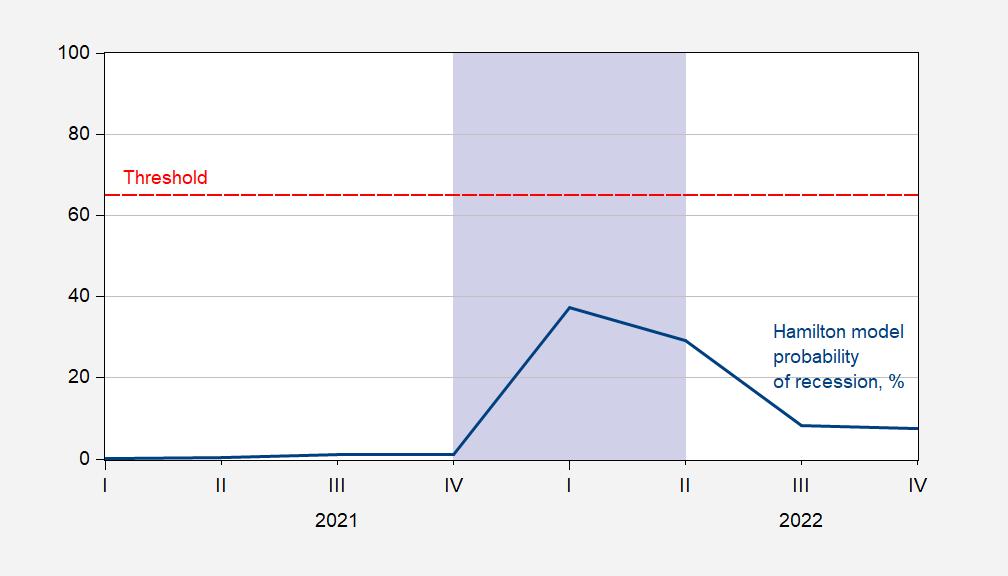

What about the James Hamilton markkov shift model for the explanation of the recession, given the decline in GDP in 2022Q1-Q2?

Figure 3: Probability of being in recession, from James Hamilton’s model, in %. Threshold means the red dashed line. Recession tolerant lilac shade 2022H1. Source: FRED.

The index remains well below the limit.

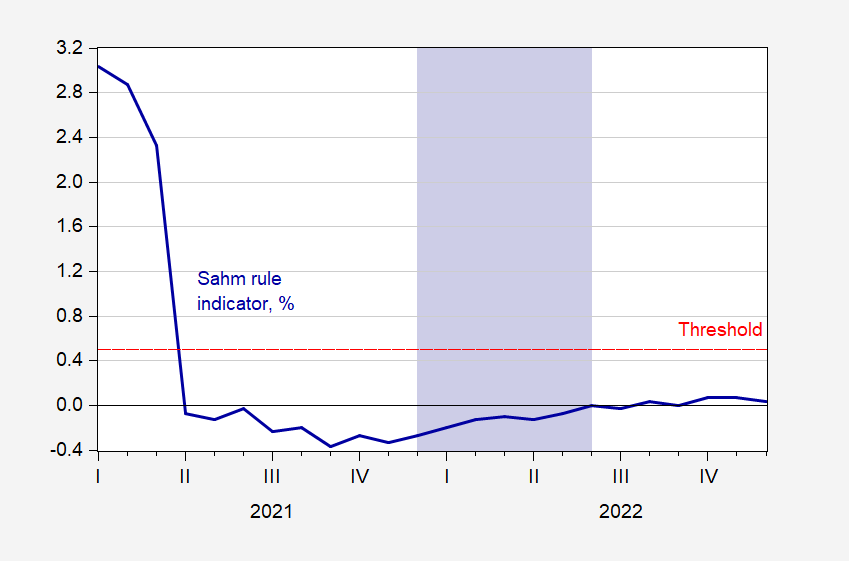

What about the law of Sahm (real time)?

Figure 4: Real-time indicator of Sahm’s law, in % (blue). Threshold means the red dashed line. Recession tolerant lilac shade 2022H1. Source: FRED.

This indicator was also far from the limit.

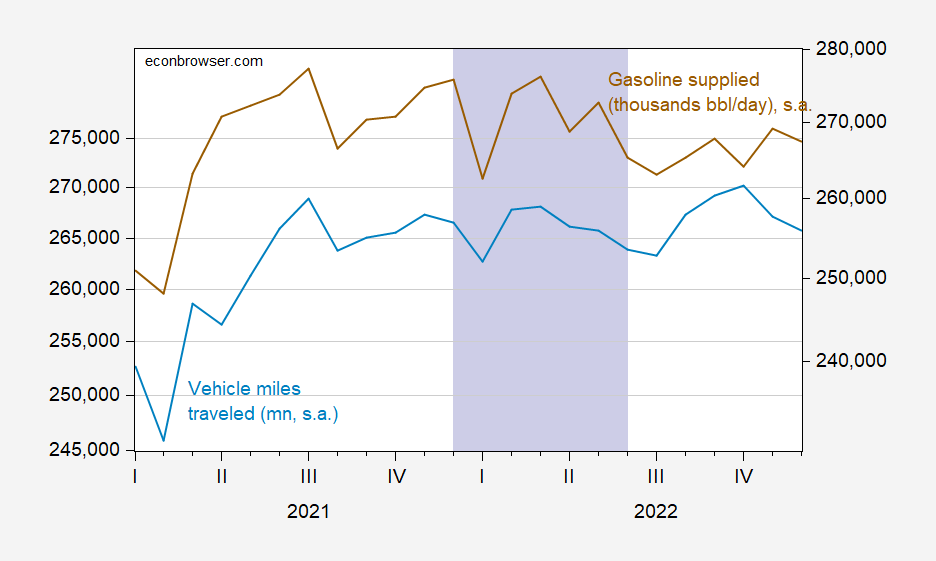

Finally, Mr. Kopits cited two series as supporting his recessionary thesis. Unfortunately, it is not as predictive of a recession as described by the NBER’s Business Cycle Advisory Committee.

Figure 5: Vehicle miles traveled, min., sa (dark blue, left scale), fuel supplied, thousands bbl/day (brown, right scale). Seasonal fuel was prepared by the author using X-13 (from logs). Recession tolerant lilac shade 2022H1. Source: NHTSA via FRED, EIA, and author’s calculations.

Remember, Mr. Kopits wrote recently September 2023:

I am very comfortable with both my H1 2022 call and the role of gasoline/diesel consumption and VMT as indicators of economic stress or comfort, as the case may be. I would note that oil and gas consumption in the US remains depressed by about 5% compared to normal but has not changed much over the last year or so.

Hey!

Source link