Yves here. Although this study has an interesting purpose, it seeks to measure changes in clothing and hairstyles as a proxy for style consistency. I doubt high school yearbooks from the 1960s and 1970s are very representative. There was a lot of opposition in schools about loose dress codes; remember girls wearing skirts above the knee (when mini skirts were fashionable in the 1960s and the original Star Trek showed a lot of leg) used to be verboten, and pants, and jeans were not allowed as school uniforms at all.

Note in particular that this study uses yearbooks from 1966 that show boys wearing suits and regular haircuts.

My father graduated from Harvard Business School in 1965 and was the oldest member of his class. When I was cleaning house last year, I found his business school photo from his class. It looked like a test shot. My father and my classmates had been shot, all in profile. My father wore a suit and had short cropped hair. Some men had sideburns and long hair and dressed as if they were auditioning to join the Beatles.

By David Yangangwa-Drott, Professor of Development and Emerging Markets at the Department of Economics University of Zurich. Originally published at VoxEU

Style choices are an important part of culture and are often used to show individuality or belonging to a group. This column uses more than 14 million photos from high school yearbooks to track US cultural change over time. Men’s and women’s styles converged from the 1960s onwards, driven by a higher independence and a lower style insistence on men. In addition, it shows that innovation in a novel style predicts levels of ownership, suggesting that cultural change can facilitate innovation in other areas later in life.

Imagine yourself wandering the hallways of a 1950s American high school. The scene is a sea of harmony: boys in trims, sports jackets and lots of ties, while girls wear fancy dresses and well-coiffed hair. Fast forward to today, and you’re greeted with a kaleidoscope of colors, hairstyles, and fashion choices that will make your head spin. This stark contrast serves as a powerful reminder that culture is more than just a set of beliefs and attitudes – it is a way of life, ever-changing and shaping society.

Recent years have seen great progress in analyzing culture as a ‘way of life’, using data on usage patterns, folklore, and naming patterns (Bazzi et al. 2020, Michalopoulos and Xue 2021, Atkin 2016). In order to analyze stylistic choices as a central part of culture, we need two things – data, and a way to make them speak. In our study (Voth and Yangagwa-Drott 2024), we use portraits of US high school seniors, 1950-2010, to track cultural change. The idea of using images as a window into social media is not new. Francis Galton, the Victorian polymath, misused composite images to create the ‘archetypal’ faces of criminals and prostitutes (Galton 1878). Thanks to the wonders of machine learning, we can analyze cultural shifts on an unprecedented scale. In a recent landmark study, Adukia et al. (2022) used images in children’s books to trace racial stereotypes. In our research, we examine more than 14 million images from 111,000 high school yearbooks to track style choices over time and space.

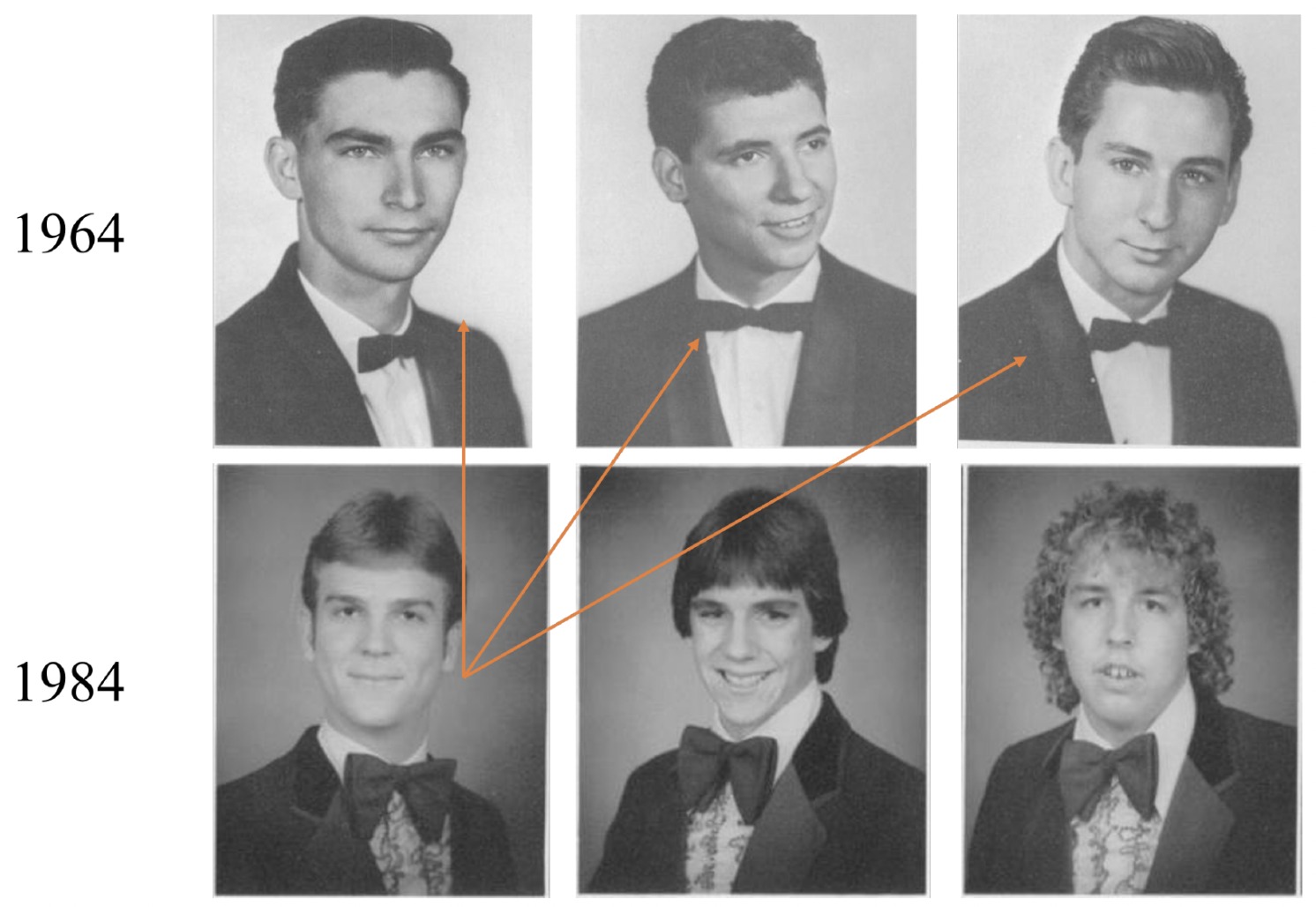

We use three main concepts: humanity (how many students in each high school dare to have a different style from their peers), persistence (similarity between current trends and those of 20 years ago), and new style (the emergence of previously unseen stylistic options). Consider Figure 1, which shows pictures of seniors who graduated from Attica High School in New York in 1966. We see that they wear very similar clothes – black suit, tie, collared shirt, no facial hair. We calculate a maximum similarity ratio based on their style preferences of 0.9. A similar style of calculation is the basis of our analysis of persistence. We compare cohorts with students who graduated from the same school 20 years earlier (Figure 2). In panel A, we have low persistence – style preferences have changed significantly. In panel B, the difference is very small, except for some exuberant bow ties and long hair. Accordingly, we calculate the maximum persistence score.

Figure 1 Individual census

Notes: This figure shows the calculation of each person’s score. For each i, it is calculated as (1-mean cosine similarity) compared to all images of other same-sex adults in the same high school group. The score for the person on the left is 0.098, indicating a low level of individual choice, as most style options (suit, hair, tie) are the same.

These indicators allow us to paint an interesting picture of cultural evolution in post-war America. Figure 3 provides an overview. The main message is that male and female style elements converged from the mid-60s onwards, as the women’s rights movement emerged and older role models were put on the back burner. Both personality and persistence levels converged in the 1990s.

Men started out in the 1950s and early 1960s with low personalities. They often looked like their parents, 20 years earlier. But as Bob Dylan prophesied, times were changin’. This ratio decreased dramatically in the late 1960s, with the growth of personality. In the decades that followed, individual choice continued to evolve into a growing trend.

In contrast, women started with more class diversity (‘individual’), then saw a decline from the 1960s onwards. At the same time, persistence began to rise from the late 1980s, approaching male levels. Both genders experienced a significant increase in style innovation. The novelty of men’s style exploded in the late 1960s, and both genders reached unprecedented levels in the 2010s.

Figure 2 Persistence

a) Low example of persistence

b) The ultimate example of persistence

Notes: The figure shows the calculation of persistence scores. We calculate the similarity of everyone in the group, comparing each of them with the style of graduates of the last 20 years (of the same sex). We then averaged these group scores. Panel (a) is an example of low persistence (0.056). Panel (b) is an example of high persistence (0.83).

We find high and similar levels of individualism and persistence in the 1950s and across all schools. However, in the 1980s, a split began. Schools were divided, some sticking to education while others embraced individualism. Perhaps surprisingly, much of the old South remained a hotbed of stylistic conformity.

Figure 3 Personality, persistence, and new style over time

a) Individual choice

b) Persistence

c) New style

Notes: This figure includes the annual average of cosine (persistence) and 1-cosine (individual) individual scores (Panel A) and persistence (Panel B); Panel C plots the share of stylists. Ratings come from our image-level dataset (14.5 million views), broken down by gender.

Figure 4 Individualism over time

Is any of this important beyond the realm of fashion and hairstyles? Should economists care about strings and ties in high school yearbooks? As it turns out, it can have significant economic implications. We examine whether the innovation of style is accompanied by innovation in technology. To set the tone, consider the story of another graduate of Cupertino high school in 1972 – Steve Jobs. Jobs appear in a bow tie and tuxedo, sporting long hair and no beard or mustache. At this time, less than 0.3% of US male students have ever worn this style, qualifying him for the ‘style innovator’ category. Jobs also applied for 1,114 patents, 960 of which were granted.

To see if the status of Jobs is normal at the high school level, we carefully match the composition of the style in the commuting area with the ownership levels of those born in that commuting area, 18 years earlier (using data from Bell et al. 2019). Tracking their successful innovation later in life, we find that areas with innovative style also see greater approval. Figure 5 shows the results – every year after graduation, students from high schools in areas with innovators are more likely to apply for (and receive) patents. While giving boys earrings and cutting Mohawks won’t increase technical intelligence, schools that embrace one of these innovations may also produce students who excel in the other. Given that innovation is thought to be a key driver of economic growth, these findings suggest that growing up in an environment with less deviance for young people may have important benefits over time.

Figure 5 Ownership of travel destinations with and without stylists, in the year since I graduated

So, the next time you flip through an old yearbook and laugh at outdated styles, remember: you’re not just looking at a sequence of fashion oddities and funny expressions, but also an important area of cultural evolution – and one that might have. serious impact on the speed of technological change.

See the original post for reference

Source link