Yves here. Yours truly doesn’t pay much attention to horses because many pundits and pundits do. But to remind readers, a major stock market crash does not trigger a broader financial crisis unless many of those positions are financed by debt. Post Big Crash changes to limited margin lending in the US, or there have been some attempts to circumvent those rules, such as equity exits, like the total return swap that created Archegos.

Sadly, it was Greenspan who put the Fed into business thinking that its job was to protect equity investors. As the Wall Street Journal revealed in 2000, Greenspan was puzzled by what determined the level of stock prices. He pointed out in 1996, when the dot-com mania began that the market seemed to be suffering from irrational exuberance. When the Dow made a swan dive, it quickly reversed and addressed the markets.

We revealed in ECONNED how Greenspan’s stock market played a role in fueling the financial crisis. After the collapse of the dot-com bubble, Greenspan was convinced that there would be a negative impact on the real economy although the recession of 1987 showed a reversal. Greenspan lowered policy rates to negative real interest rates and kept them there for nine full quarters, where the Fed’s previous practice was to lower rates only quarterly during recessions. That has led investors to seek high-yield products. We explained at length how that fueled demand for confections like asset-backed CDOs, which comprised the riskiest portion of subprime mortgage securities.

As Wolff (and even the Wall Street Journal yesterday) pointed out, investors’ enthusiasm for stocks seems unrelenting. Another problem is that the averages are unduly influenced by the high prices of large-cap technology stocks such as Apple, Meta, Google and Microsoft. However, the shares look very important, using Tobin’s Q ratio as a measure:

Finally it is worth remembering that even though the dot bubble seemed very long to the birds, it had an amazing burst phase before it went back. The trigger was bellweather Cisco’s unexpectedly weak earnings report.

By Wolf Richter, editor of Wolf Street. Originally published on Wolf Street

Nvidia, the poster boy for the stock-market mania surrounding AI and semiconductors, fell 9.5% in regular trading. In after-hours trading, it fell another 2.6% to $105.40 a share, down 11.7%. The after-hours drop came after Bloomberg reported that the DOJ had sent subpoenas to Nvidia, in an escalation of an ongoing antitrust investigation.

“Antitrust officials are concerned that Nvidia is making it difficult to switch to other suppliers and penalizing consumers who don’t use their artificial intelligence chips,” Bloomberg said, citing its sources.

Nvidia’s market capitalization — important because it’s so large — fell by $279 billion in regular trading, the most ever lost in a single day by a single company. Including after-hours trading, it’s down $342 billion, or half of Tesla.

But it’s not a big deal because easy come, easy go, and Nvidia had similar one-day steps on the way to the top. The stock is now down 20% from its July 10 high. And Nvidia wasn’t alone.

Semiconductor bleeding during normal hours includes:

- Nvidia [NVDA]: -9.5%

- Intel [INTC]: -8.8%

- Marvell Technology [MRVL]: -8.2%

- Broadcom [AVGO]: -6.2%

- AMD [AMD]: -7.8%

- Qualcomm [QCOM]: -6.9%

- Texas Instruments [TI]: -5.8%

- Analog Devices [ADI]: -6.5%

- ASML [ASML]: -6.5%

- Materials Used [AMAT]: -7.0%

- Micron technology [MU]: -8.0%

- NPX Semiconductors [NXPI]: -7.9%

- The KLA [KLAC]: -9.5%

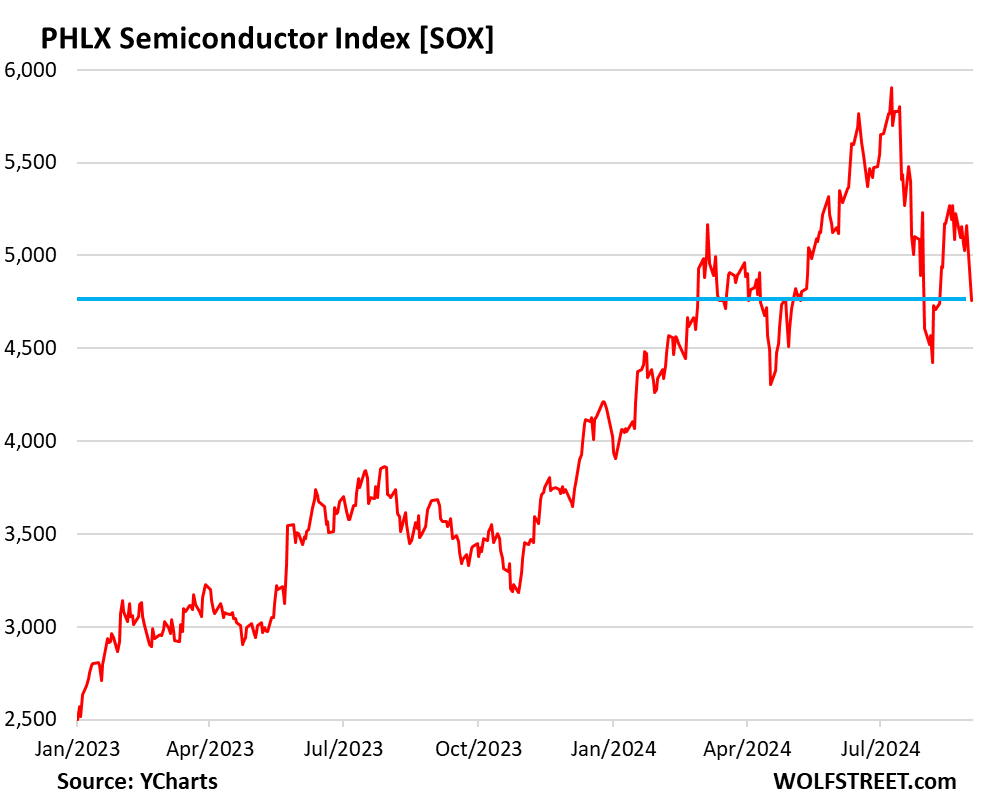

VanEck Semiconductor ETF’s lowest price [SMH] down 7.5%, the biggest one-day decline since the March 2020 crash. PHHLX Semiconductor Index [SOX] decreased by 7.8%. So that was a good day’s work on the first trading day of September:

It wasn’t any kind of economic news, like a sudden drop in consumer spending on Labor Day or the collapse of three major banks on Friday evening or an AI prediction that the world is going to end, or whatever, that killed semiconductor stocks — and to a lesser extent stocks more broadly, the S&P 500 fell by 2.1% today and the Nasdaq Composite is down 3.3%. Instead of falling, the consumer does well, and returns to the punchbowl for refills.

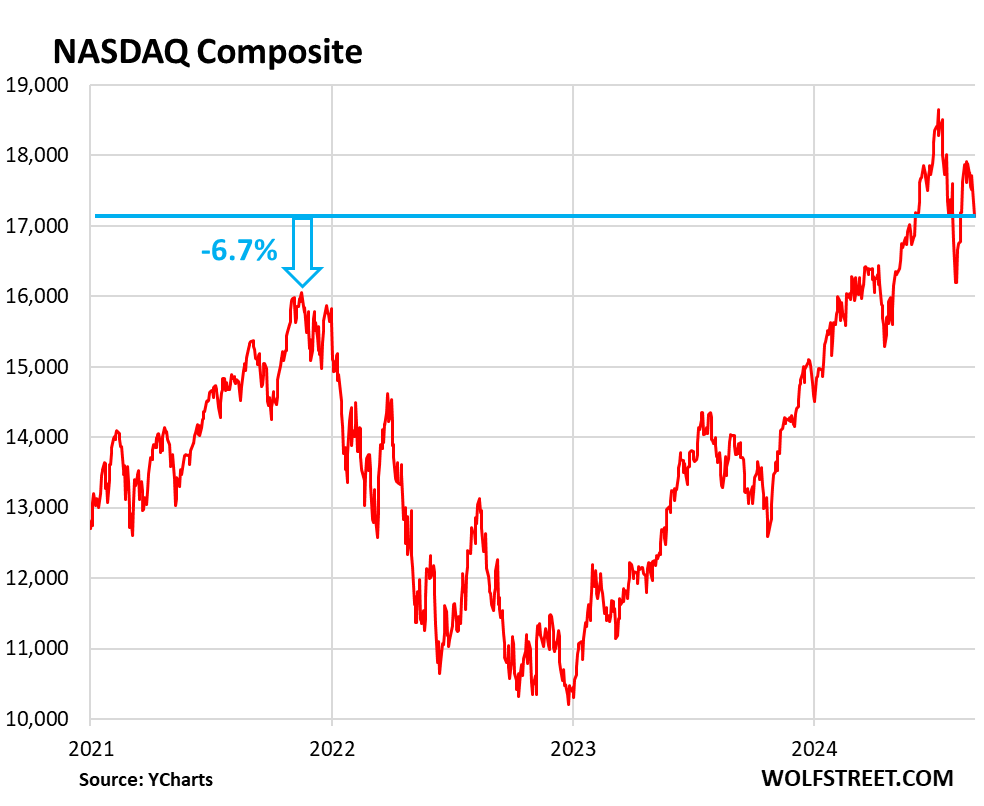

So the Nasdaq composite fell 3.3% today to 17,136 and is down 8.1% from its all-time high on July 10.

If it falls another 6.7%, it will return to where it started in November 2021, with a big sell-off and a production meeting in between. T-bills have done better than that since November 2021, but without all the fun and drama.

Action from July 10 is not a good idea:

It’s just that Americans have been more bullish than ever on stocks, after years of big rallies in which the allocation of housing to stocks as a share of their financial assets reached a record high of 42% in Q2, easily surpassing the then-record 37% in Q2 2000, according to JPMorgan estimates. mentioned by the WSJ.

Q2 2000 was of course the time when stocks began the Dotcom Bust that would eventually drop the S&P 500 by 50% and the Nasdaq Composite by 78% over the next two and a half years, after which it took 13 years for the Nasdaq. , including years of QE and 0%, to surpass its Dotcom Bubble peak.

But investors now consider this irrelevant. It will never happen again. Stocks will always go up. The Fed will restart QE every time stocks dip a bit, etc., etc. As investors are overexposed to stocks, especially over-the-top stocks with ridiculous valuations, such as Nvidia, and overconfidence that the stock will continue to rise, if anything moves. and the selling pressure increases suddenly, so there are not enough strong souls left willing to buy at these ridiculous prices, and the next layers of buyers – dip buyers – will have to be lured by even lower prices. But that has been a tough game lately.

Source link