Lambert here, freely speculating: World systems analyst Giovanni Arrighi argued (I’m memorizing) that the “center of gravity,” as it were, of capitalism moved in a circular pattern from West to East, starting in Italy, and then left. in the Netherlands, Britain, and the United States, and in the future he will travel across the Pacific. Assuming he is right, it would be an interesting comparative study to find out if the patterns of state and society changed to match those described here in Florence in each new center, as the capital moved to the East. Maybe we have a political economist in education who can correct me.

By Marianna Belloc, member of the Network at Cesifo, Full Professor of Economics at Sapienza University Of Rome, Roberto Galbiati, CNRS Professor of Sciences Po Paris, and Francesco Drago, Professor of Economics at the University of Catania. Originally published at VoxEU.

The Medici family ruled Florence for almost 300 years, supporting the arts and making Florence the cultural center of Europe. But there was a dark side to the Medici rule. This column examines the circumstances in which a more open political system can be undermined by dealing with concentrated wealth. Without formally changing the constitutional structure of the political system, the Medici machine manipulated its institutions and allowed political officials to accept public funds, transforming the holding of office from a public function to a source of individual wealth accumulation.

In September 1433, Cosimo de’ Medici, founder of the Medici dynasty, was summoned to appear before the Signoria, the government of Florence, to be informed of his banishment from the city. This decision was caused by allegations that Cosimo tried to manipulate the results of the election of members of the government. In response, Cosimo famously remarked: “Ask your soldiers how many times they have been paid with my money, the Council only paid me back when you were able to do so” (Molho 1971). Cosimo was one of the richest men in the city, the leader of a successful bank with branches all over Europe, and the main creditor of the Republic during the great financial depression.

A year later, Cosimo was returned to Florence. He controlled the city, marking the beginning of the Medici rule, a rule that would last in various forms for nearly three centuries. The political machine built by Cosimo, without formally changing the constitutional structure of the political system, produced a systematic exploitation of its institutions and allowed the distribution of public resources in a systematic way by political officials. This historical episode took place six centuries ago, yet its impact applies to current vehicles, providing a warning about the conditions in which relatively open political institutions, with checks and balances on political power, can be caught and changed drastically in the face of strong political convergence. wealth.

In the economics literature, research on the effects of the concentration of wealth on politics focuses on various aspects within the broader field of institutional capture. In their study of Venice, Puga and Trefler (2014) document how formal elites can transform institutions into political closure; other scholars, such as Dal Bo (2006) and Glaeser et al. (2003), investigate how officials can influence institutions to work for them. Florence’s case lies between these two extremes: it shows how close political control can be achieved without formal institutional overthrow and it shows the consequences of this subtle but profound form of institutional capture. It is a sign of how political monarchies can emerge and survive over time, a situation that can be found in current democracies (Mendoza 2012).

In Belloc et al. (2022), examine this historical episode, document methods to capture the institution and the associated economic returns of the electorate, and examine its implications for the distribution of wealth.

The Republic of Florence was founded in the 12th century. Between the first half of the 14th century and the end of the 15th century, access to city government was controlled by a system that included elections and selection by lottery. This program, called Trattecombined with the short term limits of the office bearers, ensured a relatively broad participation in the city government, ensured a moderate balance of power among all prominent families, and limited rent extraction for several decades. The arrival of Cosimo de’ Medici and his family in the political arena marked a turning point.

From the 1420s, the city took part in the wars of Lombardy, incurring huge military costs. The pressure of the subsequent financial crisis required major changes in the tax collection system, which involved widening the tax base and establishing a mechanism for direct lending of money to citizens by the Government. These events stimulated a growing need for inclusion in the city government, but also gave rich people the opportunity to become creditors of the Republic (Molho 1971). From these lenders, Cosimo used his money to build a network of patronage and credit relationships (Padgett and Ansell 1993). Opposed by the leading families of the previous government, the Medici used the bargaining power generated by their position as holders of public debt and lenders of resources to seize political choice and seize control of the city. Figure 1 shows the percentage of debt owed to the Republic by the opposing political parties between the 1420s and 1430s: it shows that the availability of movable wealth was closely related to the contribution of public debt, and that part of the credit held by the Medici network. about half of all credits.

Figure 1 Loans to the Florentine Republic by political party, 1427-1434

Notes: Bars (left vertical axis) measure the share of total debt provided as voluntary loans to the Republic between 1427 and 1432 by political participation. The dots (vertical axis on the right) show the average liquid property in relation to politics. Above each bar, the corresponding individual loan is reported (in 1427 gold florins). The shaded area of the third bar refers to the share of credit given to Cosimo and his son Lorenzo.

The source: Belloc et al. (2022).

Our research relies on a unique dataset compiled from archival and secondary sources, including a global wealth assessment of Florentine households in 1427, 1457, and 1480, as well as detailed information on family group affiliation and individual political participation during the 15th century.1

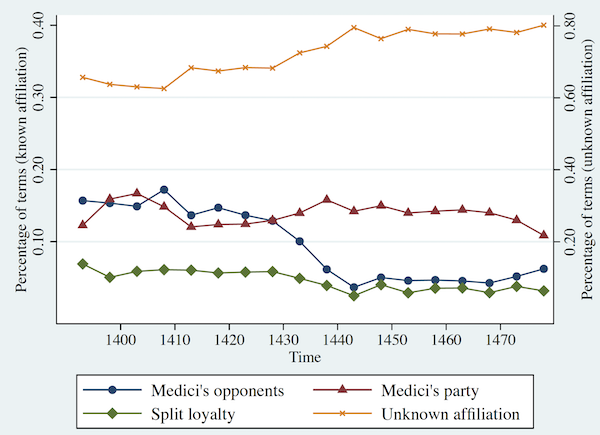

Based on this dataset, we show that the Medici capture of Florentine political institutions involved manipulating the system of selecting office holders in favor of members of their own party. After the Medici came to power, being a member of their party came with the chance of being elected to public office, while the chances of the Medici’s political opponents dwindled. Figure 2 shows the relative frequency of terms of office by political party and five-year intervals during the interest period. As can be seen, while the political presence of different peoples remained stable during the century, the presence of people close to or against the Medici varied greatly after the end of the 1420s.

Figure 2 Relative ranking of terms of office by political party and five-year intervals

Notes: The lines show the relative frequency of office terms by group and five-year intervals. The vertical left (right) axis refers to specific known (unknown) individuals.

The source: Belloc et al. (2022).

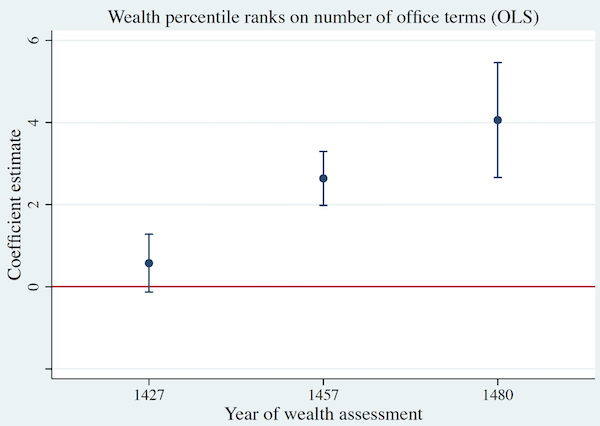

Our data also allow us to track how political participation relates to changes in individual wealth over time. As shown in Figure 3, before the Medici took power, the number of words a person spent in office (measured in the period 1393-1426) was not significantly correlated with the accumulation of wealth per person (1427). Conversely, after the Medici took control of the political system, the correlation between holding office (1427-1456 and 1457-1480) and wealth (respectively, 1457 and 1480) increased significantly.

Figure 3 Political participation and individual wealth status

Notes: The graph plots the OLS estimated coefficients from the decline in per capita wealth (1427, 1457, and 1480) in terms of per capita in office (respectively, 1393–1426, 1427–1456, and 1457–1480), straight lines showing the confidence interval. 95% level.

The source: Belloc et al. (2022).

The data presented above and the results of other experiments used in the paper suggest that the institutional capture of the Medici turned active political participation into a vehicle for personal enrichment. And this system was innocent in spreading all the wealth. In fact, although the political institutions did not officially change, hundreds of people who participated in the city government saw their wealth increase each time they were in office. We find that the accumulation of wealth at the top of the distribution increased after the Medici consolidated their power, as the dynamics of wealth accumulation favored families connected to the Medici over families outside their network.

We identify two main ways in which political officeholders could extract rents under the Medici: the direct allocation of public resources and the use of their political role to develop patronage networks for their own benefit (Padgett and Ansell 1993). Allocation of public resources and funding, although difficult to document, is not common in current political situations (Prem et al. 2019, Labonne and Fafchamps 2016). Government officials aligned with the Medici were able to use their positions to obtain favorable loans, contracts, and other financial benefits. In our paper, we show that during the Medici regime, and not before, the Republic paid high interest rates to households with large numbers of positions.

We conclude that the Medici seizure of Florentine political institutions had significant economic consequences. The political office held in Florence in the 15th century had long been a public office of little personal economic benefit; under the Medici regime, it became a source of individual wealth accumulation. This change contributed to greater wealth inequality, which in turn enriched the political party at the expense of the communities. The Medici were patrons of the arts and contributed to making Florence one of the most important cultural, economic, and political centers in Europe. This is the main reason why their name remains famous all over the world. However, as we show, the Medici legacy is associated with the personal use of public office and the perpetuation of inequality. What happened under their regime is similar to many situations that can be found today, where economic and political power collide, creating vicious circles of wealth inequality and abuse of social position.

References are available at the beginning.

Source link