By Lambert Strether of Corrente.

Readers will recall the previous two posts in what became this series: My Life So Far in Writing Tools, where the tools were analog printed books, like the OED, and My Life So Far in Type, where textual type began. physical (typewriters), then analog (phototypesetters), and finally digital (AM Varityper). The transition from analog to digital began at the keyboard and ended inside the printer, culminating in a workflow that was in bits (nary digis) from start to finish (except, of course, for the decimal digits of my hands). At the time, these stage changes were seen as changes in the flow of my workday, as I hopped from job to job, like Eliza jumping across the Ohio River from ice to ice (embarrassingly, whenever I “reach” for “Eliza” I always hold “the memory of -Motown’s Little Eve. Looking back, I was struggling with the big changes, as all the new industries – starting with Silicon Valley! – came to an end.

After a short time as a production manager, still working in printing, I ended up in a printing house as a part-time hand-glued artist, because I felt that I wanted to work on my writing. This was again in vain – my university friends had long since dispersed – but for some reason I ended up at a trade show, where I saw a Macintosh. There were newspapers in those days – racks of printed magazines you could stand and read, outside indeed shopping – and Cambridge (down, or up the red line from Boston) was famous for them. There I read computer magazines, and I noted with interest that now there were computers dedicated to doing whatever the AM varityper did (there was no word for that at the time), but smaller, simpler, and cheaper. Hmmm….

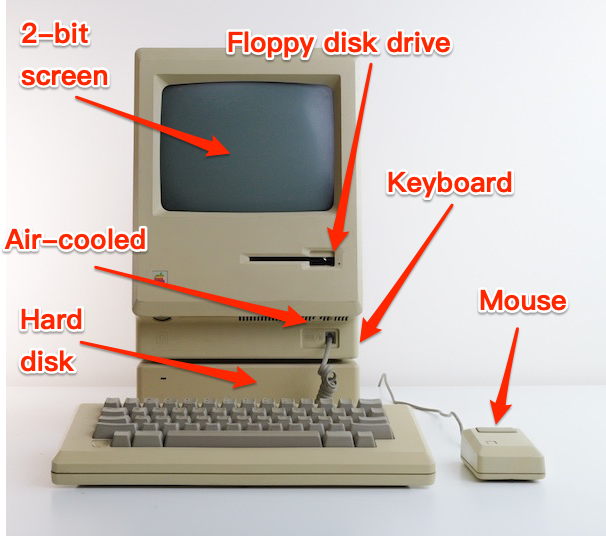

The Apple Macintosh (“Mac”) I saw was something new, different from the AM Varityper, different from everything in the magazines, although it had all the same features: Keyboard, monitor, disk drive, etc. It looked something like this. this:

There was a rainbow logo, which didn’t look like business (the winter white of Apple’s latest beauty hadn’t appeared yet). In addition, the Mac was clear it is designed; the curvaceous but beautiful “Hello” reminded me of my family’s friendly and loyal VW bug (and Mac users, for a long time, used to greet each other in passing, like VW drivers). In one, there were what I read were called “applications” – MacPaint, a program that allows you to draw pieces on the screen to create art, was one such, but there was MacWrite, which allows you to do something called “word”. it is being processed.” Best of all, there was fontsfonts come in roman, bold, italic, and bold italic (all bitmap on screen, and rough if you look closely). My reading of the newsstand, however told me that the floppy drive was not enough to do the real work: I found out that there were actually “tips” – an ecological system of printed magazines, supported by Apple’s advertising, was quickly appearing – on the correct way to hold a new floppy disk so you can install it quickly when you remove the old one. My AM Varityper disk was big, and the drive was klunky, but I never did that! So I waited….

Just in time, the Mac 512KE – so named from 512 kilobytes of RAM (my current Mac has 16 gigabytes) – came on the market. Since I was very poor, I went to the employers, and they released me (generously, considering my difficulties at school, and wisely, since the gift put me on the way to several real jobs, including this one). I ended up with a machine that looked like this (with some modifications):

I brought the boxes home to my Somerville house under the cover of darkness, and placed the machine on the table I had built. Then I sat down in my artist’s chair and turned it on (“started it”). Nothing. In fact, two days nothing. And on the third day, I accidentally pulled out the mouse – the AM Varityper didn’t have a mouse – and the screen came to life! I discovered that the machine had a version of Pong, controlled with a mouse, and for two days I did nothing but play Pong. Then I thought “Wait a minute,” I stopped, and since then I have never played a computer game (on my machine or any other).

About the naming of parts: The legendary Steve Jobs apparently hated fans, so the Mac, like our VW bug, was air-cooled. The screen had two bits, one black, one white (zero and one in the machine’s RAM). If you looked closely, the entire screen image was a series of black and white dots, and — amazingly! – the dots (I read) were 1/72 of an inch, like the categories of my pica ruler. A floppy drive took large disks, but I also got a hard disk (I forget the type, but it held very large data: 10 megabytes; enough for half a RAW file these days, but enough at that time for the processing of many words. files ). The keyboard was extremely odd after the professional feel of the AM Varityper, and it felt weird and creaky – like most Apple keyboards then and there, if the truth be known – but at least it wasn’t. mushy. It didn’t click; it exploded. And then there’s the Doug Engelbart-style mouse (from the tail-like string, I think):

A mechanical mouse has a ball in its belly, and as you move the mouse, the ball rolls. Small rollers inside the mouse detect this movement and send signals to your computer, telling it how far the mouse is moving and in which direction. This information is then used to move the cursor on your screen accordingly

All is well and good, except the ball (rubber, of this version) picks up anything that rolls, so from time to time, when the movement of the mouse begins to collide and find a random, rubber ball. it had to be cleanedwhich had a major ick factor; I still shudder when I think about it.

Fonts and pica-friendliness of the screen led directly to what was called “desktop publishing,” where the Mac did all the Setup Department, Art Room, and Page Makeup Department, inside the computer, in one application. If you already understand the words of the type, the geometry of the page, and the common language of the publication, it was unusually easy to produce in a fiery way, which I did (thanks also to the generosity and wisdom of my parents; I didn’t have to ask again).

But this post isn’t about the desktop publishing branch of my so-called career path (although I loved that job as much as hand-gluing).

This post is about writing.

After I got a computer, I joined a computer group and started attending meetings. The group was run entirely by volunteers (here we remember the authors of the Macauley Library and the authors of the OED). One thing the volunteers did was writing (meeting reports; reviews) so I volunteered to do that.

My difficulty in writing, either with pen on paper, or with a typewriter, might be called Rathole Blockage. I would start with quick words, get a few paragraphs and then have a few pages, but I would always come across a topic where I needed to dig deeper, and then deeper, deeper, and it seemed that there was nothing. way to get myself out of the rathole and move on, so I stopped. I will never finish anything else! I was too young to know about Vladimir Nabokov, who invented index cards, or PG Woodhouse, who wrote (supposedly) on a piece of paper, then attached sheets of clothing to strings hanging from the ceiling. Both techniques allowed for re-organization, which I needed, but I didn’t know I needed – I blamed myself for thinking too clearly – and I didn’t even know it was possible.

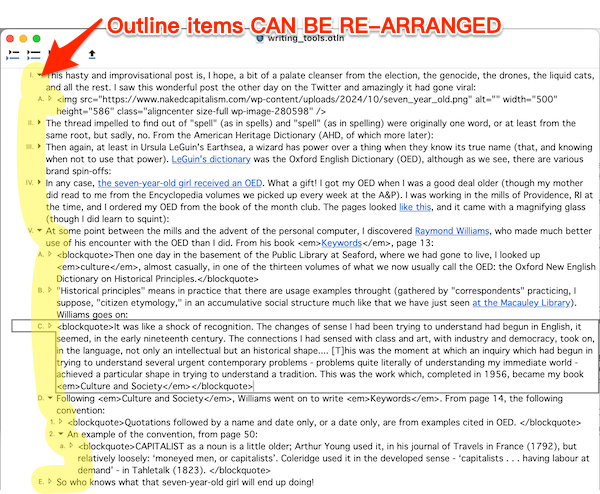

Then I discovered that there is a Mac Desk Accessory (sort of a widget) called Acta[1]. Acta was a draftsman, and made a draft as he had no doubt been trained to do at school. Rather than explain what an outline is, I’ll present part of the outline of the first post in this series, My Life So Far in Writing Tools:

As you can see, the outline items are numbered in Harvard style (I., A., 1., a., etc.), although I delete the numbers (unless I want to number the sections), because the indentation is enough to show the structure.

Important point: Frame objects can be rearranged. I could just write down the script, in any form, to my liking, and then polish and re-edit until the work was done. That cleared the Rathole Blockage. I can finish! The first time I used Acta, I completed a report. On the same day, I wrote a product review. The feeling was good. I continued to write a lot more.

So, to the extent that writing can be art, and to the extent that I can, I owe my art to the Mac, to the Acta writer, to the digital transformation that created both, and. Of course many, many years of changing words into type before that[2]. I can finish!

READER NOTE

My identity, at this point, is full of holes, now that I’m autobiographical. However, I would be grateful, dear readers, if you could guess about “my life” in the comments, or in the institutions and places mentioned in these articles. There is no need to make life easier for Google than it already is. Thank you!

NOTES

[1] Desktop Utilities went away when Mac OS became Unix-based. Acta author David Dunham wrote an incredibly simple Opal outliner, which is no longer maintained (and I dread the day when so-called development causes my one important application to fail). Microsoft basically killed the product category by putting a crude and ugly display on the Microsoft Word bloatware. (I believe in this post I am also setting the record straight; this history of outliners, or this one, does not mention Acta or Opal. [2] Which is one of the reasons I em use a Mac, despite the fact that the user interface and keyboard shortcuts are hardwired into my muscles, my nerves, and my brain.

Source link